A day for plastic patriots yesterday, the day that many, possibly most people now don’t know, with people who wrap themselves in the flag and bang on about the war first and foremost. In 1945, yesterday was the last day of the Second World War. It was supposed to be May 7th, not May 8th, but Stalin wasn’t up for sharing a peace deal with anyone else, so far as I understand it.

It was, according to an US fighter pilot I used to know, the first day of massive drinking that lasted weeks, and an immediate two weeks of leave granted to pilots as suddenly the US Army Airforce didn’t have much use for their services, at least in Europe. A lot of the drinking, he said, was because the war was over so they wouldn’t get killed. A lot more of the drinking, he said, was because they thought they’d all be sent to the Pacific to fly ground-attack for the invasion of Japan, so they’d all get killed anyway. Meanwhile, there was drinking to be done.

The date probably accounts for an Instagram post I saw today, bizarrely put up by an account called IamSophieScholl, by someone who is demonstrably and easily proved not to be Sophie Scholl, given that she was beheaded in 1943. I thought maybe it was her anniversary too, but no, she died in February. Her name is next to unknown in Britain, chiefly, I think, because it interferes with the accepted narrative.

They all knew what was going on

My step-brother in law came out with this idiotic statement years ago. It’s stuck in my mind ever since. I asked him if he saw his neighbours being beaten up by the police, the street full of marked police vans, people in police uniforms kicking the door down next door, dragging the neighbours into the street then putting them in a marked police van, never to be seen again, what he would have done. Called the police?

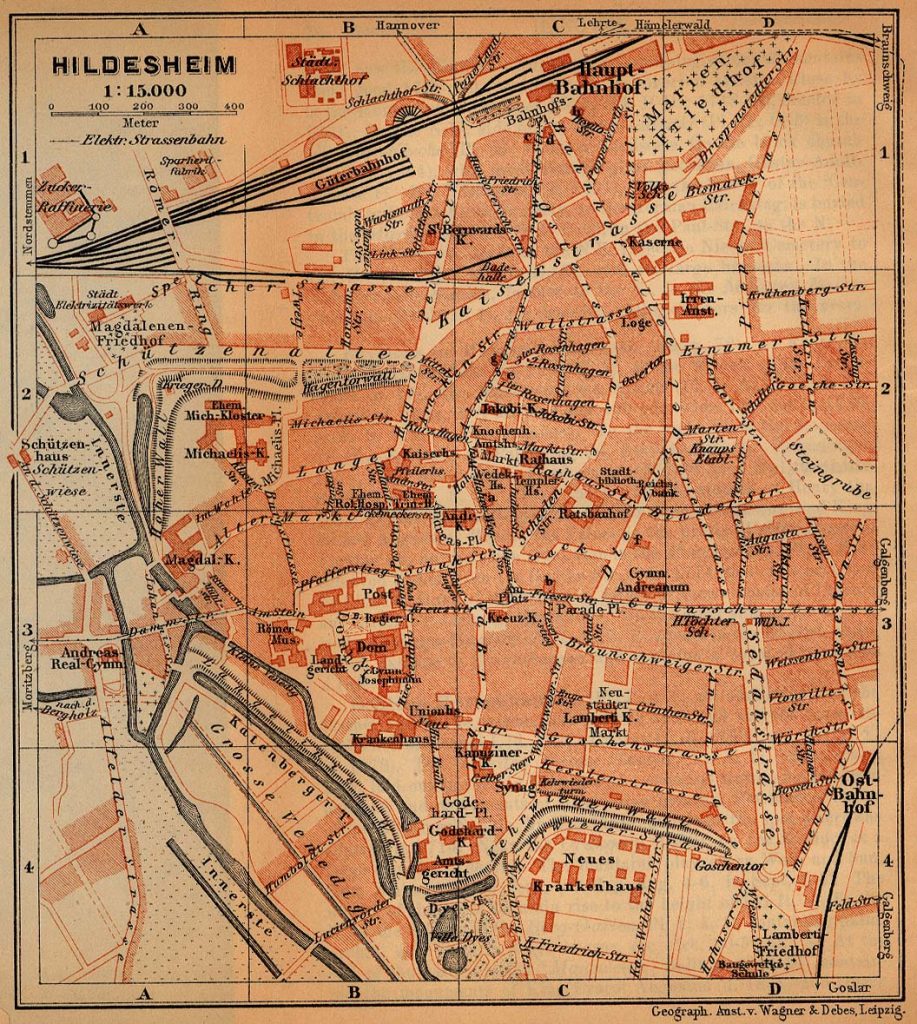

But it became a handy trope to justify the behaviour of the Allies, and handier still to justify the deliberate destruction of every German town of any size. I used to know, as it were, a woman who was born long after 1945 in a place called Hildesheim.

Before.

You almost certainly won’t have heard of it. There was never anything much there. A grass airfield that Luftwaffe squadron KG200 used a couple of times, flying a captured American B17 bomber to drop Nazi agents into parts of Germany over-run by the Allies. A factory that made optical lenses. Not in any sense an important military target. Not even strategically important, on the plain southwest of Hanover. It didn’t matter.

There were seven previous occasions when Hildesheim had been bombed, but March 22nd 1945 was the big one. The Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command issued an order which was very specific: “to destroy built up area with associated industries and railway facilities.” You might want to re-read that carefully, as it’s the exact text.

“Destroy built up area.”

And associated industries. Not the other way around. What it specifically doesn’t say is the fantasy propagated by countless films, TV series, books and Brexiters – we were noble, mate, we didn’t bomb civilians deliberately. It was unfortunate they were there. But that’s war. Where also the first casualty is truth.

The orders for Hildesheim show that to be the total and utter lie it always was. German houses and German civilians were going to be bombed because …well, because they could be bombed. We don’t want all these bombs going to waste, do we? They didn’t build themselves, you know. What do you suggest we do otherwise, chuck them in the sea off Ireland or something?

Almost three-quarters of the houses in Hidlesheim were destroyed overnight, by 250 British airplanes. Fifteen hundred German people were killed. Five hundred of them have never been identified. They couldn’t be.

But today, seventy-six years ago, it had stopped. In theory, anyway. A couple of German units hadn’t heard of the surrender, stuck on the shores of the Baltic. A couple of U-boats had heard and were heading for South America.

But for most people in Europe, it was over. If there was no other benefit of the entire EU project, keeping it being over alone would be enough to justify any amount of contributions. But we forget, just the way we were told to. Just the way we pretend not to.