Two days ago I had my AstraZeneca anti-Covid injection. For the first day my arm was a bit tender where the injection went in, and I ached a bit, pretty much all over, with a slight headache. I felt as if I was dehydrated, but judging by urine colour, I wasn’t. It just felt like a mild dose of flu, but without the hallucinations and conversations with Marine Boy.

Last early night I was on Facebook and saw that the local fire station was doing asymptomatic Covid tests. We booked at about 10pm, online, found a slot at 0800 this morning and went along and got tested. It took five minutes for the test. It didn’t hurt. And I found that today I don’t have Covid. Which was nice.

I didn’t have any symptoms I couldn’t easily explain as the effect of the injection. I didn’t have a cough. I didn’t think I had a temperature to the extent that I didn’t bother to root the thermometer out of the cupboard and find out – it didn’t actually cross my mind.

So why test? For me, it was obvious. As someone who has stopped teaching partly because I refuse to be sacrificed to Covid on the alter of Boris Johnson’s ego, I’m extremely interested in the idea that people who don’t think they have anything wrong with them actually do and can go on to die of it. Unapologetically more importantly they might give it to me.

The other reason, obviously, is if asymptomatic transmission of the virus is a thing, then the only way of knowing what proportion of people have it is to test people, whether they think they’ve got it or not. As the house magazine of the British Medical Association put it, by failing to integrate testing into clinical care, we’ve missed an important opportunity to better understand the role of asymptomatic infection in transmission. So far in the world-beating UK, we’ve managed to take an entire year missing this opportunity.

You go to the testing station and queue up a safe distance from the not very many other people in the queue. There’s time to look at the mangled cars the firemen take to pieces and see how high the practice tower is. Rather quaintly I thought, it had proper light switches on it.

You’re given a slip of paper with a bar code on it and two bar code stickers. Do not do what I did and stick one on your notebook so you don’t lose it; it’s not for you anyway.

Top tip: The sticker will come off without ripping if you do it slowly.

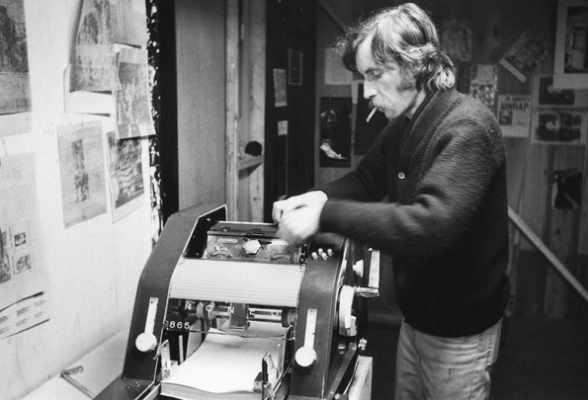

I totally messed-up logging on to the website to put my details in. It all looks at first glance as if it’s very high tech but if that’s seriously what £200 billion buys then someone’s done very nicely out what could have been done with a box of pencils and a Roneo-Vickers copier full of pink ink, the kind that was cutting edge when I was at school.

It doesn’t hurt

The lateral trace test isn’t a blood test. There are no injections, no blood, no rolling your sleeves up or anything like that. There was some massive confusion though. The tester obviously wasn’t a doctor, but he didn’t need to be. What he did need to do was speak a bit louder. I couldn’t hear him through his mask and when I did he made no sense.

Do you know where your tonsils are?

I’m old, ok? That’s why I don’t want to die yet. It’s also why, it is submitted m’lud, that when I hear a question like that I grab the first thing that comes out of the grab-bag of associations and random historical artefacts I call my memory. Which was this picture.

I last saw my tonsils over *cough* years ago. I don’t have any. They were taken out at the Royal United Hospital in Bath, which is what happened to almost everyone’s tonsils back then. I imagine, although I don’t know, they went into the incinerator there. But I don’t know. So I can’t answer this presumably vital medical question. I asked him to say it again in case I’d misunderstood.

Nope. That’s what he’d said. Do I know where my tonsils are? No. I still don’t. I know where they were, but that’s a completely different thing. Once we’d cleared that up we got down to the unpleasantness, such as it was.

You’re asked to sanitise your hands. Then blow your nose and chuck the tissue in the bin provided. Sanitise your hands again. You’re given a swab, like a cotton bud from the pound-shop, but longer, much thinner and I’d guess, as there is one per sterile pack for one use only, rather more than a pound. You’re asked to rub the swab up and down your absent tonsils (or in my case, where they used to be once upon a time in a land long ago) four times. Then stick it up your nose and rotate it ten times. Not nine. Not eleven. I thought that was rather sweet. The gagging I couldn’t help doing when I stuck the swab in the back of my throat, having no tonsils to act as a guide, wasn’t rather sweet, but that was as unpleasant as it got.

All done, go away. You get an email half an hour later. I’m clear. Today, anyway.

It doesn’t hurt. It doesn’t cost you anything. It’s essential it gets done if we’re going to have any real idea how many people are infected, if people can be infected and more importantly can give the virus to other people, without knowing they have anything wrong with them at all.

But there are things wrong with all this. It’s very wrong this is only being done now. It’s utterly ludicrous that this Track and Trace programme has taken a year to roll-out. It’s absolutely farcical and yet somehow predictable now in England, that the only way I knew about the test even being available was by being on Facebook at the right time, totally by accident. I’ve heard nothing about it on local radio, national radio or the local newspaper website. How that’s supposed to be effective is unclear.

What also isn’t clear is how NASA spent $2 billion on a rocket to Mars but in the UK it costs £200 billion to stick a baby bud up your nose. It’ll be a world-beating reason, whatever it is. Obviously. You have the Prime Minister’s word on it.