I did, but I think I got away with it. I’d written a screenplay that actually got as far as being considered for the Cannes Film Festival (before being placed, possibly even gently, in their Trash folder) by the Maison des Scenaristes, of which I was a member, hem hem.

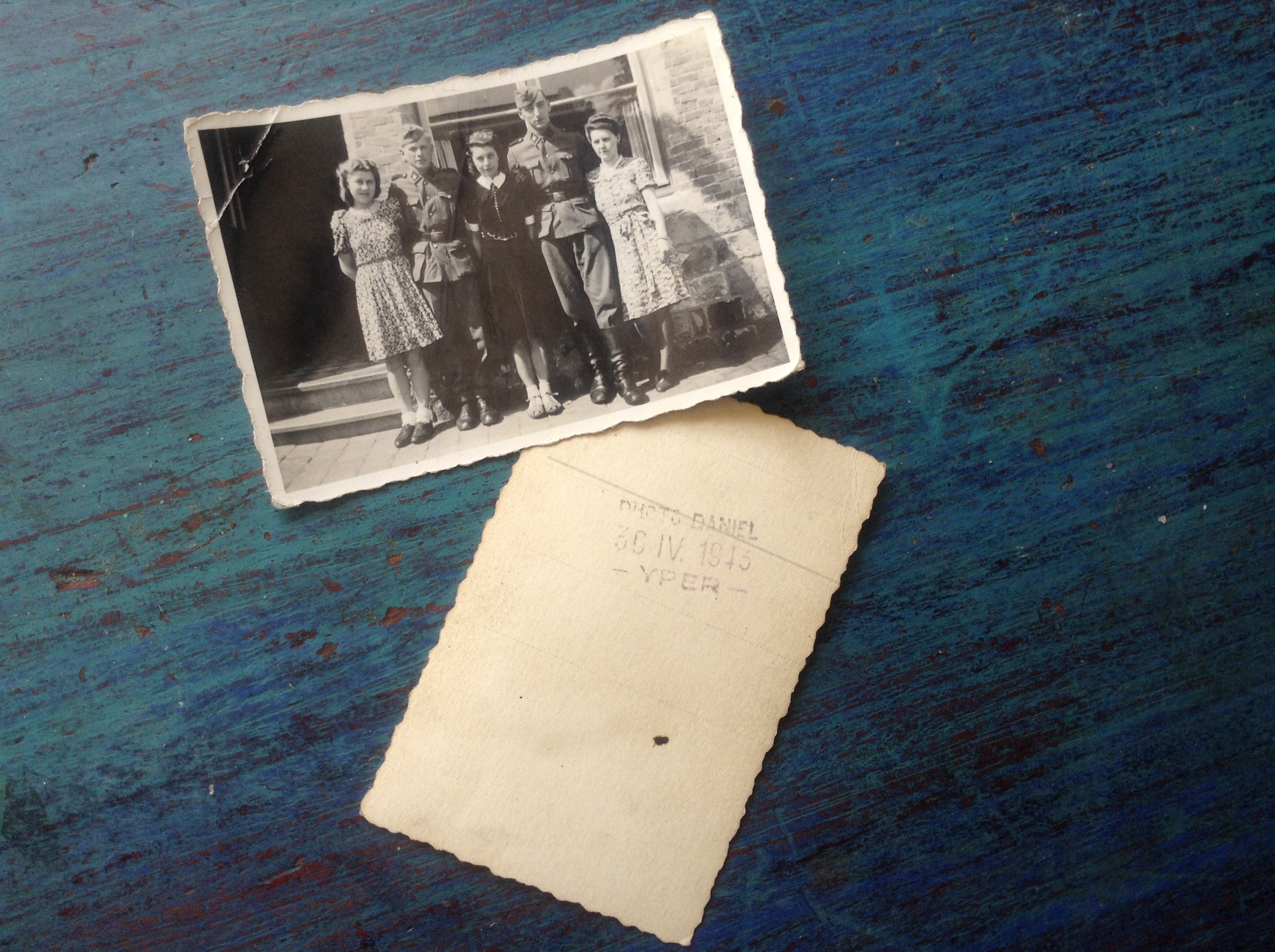

It was a blend of two true stories, one I’d heard at first hand. Somehow in my life I’d separately met two very old men who had both been in the Hitler Youth. Both of them said the singing, camping, Strength Through Joy part of it was absolutely brilliant, it was the giving up your life for the Fatherland in 1945 that was somewhat problematic, which was exactly what one of them was told he was doing when the American army rolled up to his village. A girlfriend’s grandfather had been a surgeon in the Wermacht Heer stationed in Czechoslovakia. Very early in 1945 he laughed at a joke about Hitler and as a result was sentenced to death, as was his colleague who told the joke. I called the boy Janni Schenck.

Janni Schenck

He lived when his schoolteacher, who was supposed to be the head of the local Jugend gruppen, assembled the boys on parade, beat them up, made them throw all of their guns in the ditch and sent them home crying.

The surgeon lived when as he and his friend were being taken out to be shot partisans attacked, the friend said “Run!”

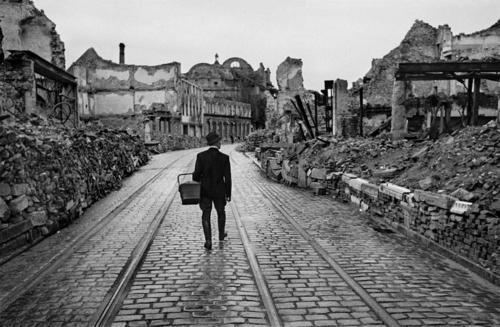

He didn’t stop running until he got home to Bremen, past Gestapo and SS death squads, past the fires of Dresden, afraid to move in daytime thanks to the RAF and USAAF blasting anything that moved on the roads, without papers or food and starting only with a shirt, jacket and trousers. It’s over 900 miles.

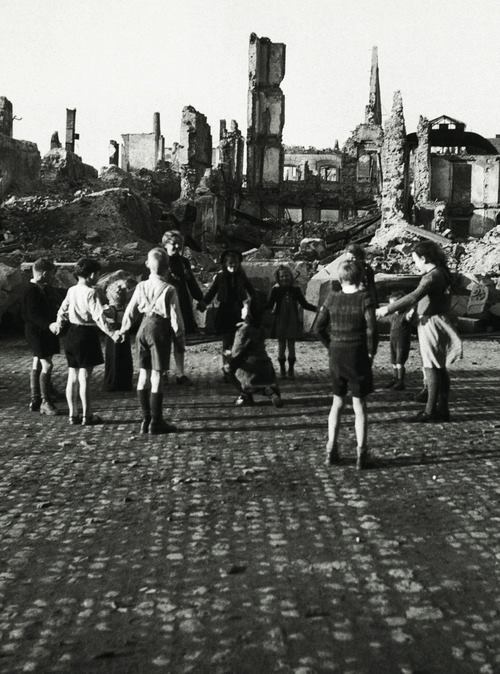

Those stories are being lost with time, as they always are. I wanted to write something that remembered them, not as glorious warriors but people who had nothing left except hope, who somehow built a decent life and a decent society out of the smashed rubble of hate the previous generation had made. I combined their stories and had the surgeon turn up in the boy’s village just after the schoolmaster had prevented the village from being massacred and gave it to a friend to proofread. She gave it back a week later, saying it was good but she never wanted to read it ever again.

She told me most of her family had been killed by boys like Janni. She thought nobody wants to read stuff like this anymore. It wasn’t relevant. And not everything is about what people of our age call The War. That was before JoJo Rabbit. And before tanks started rolling across the Ukraine again.

Something better change

The Stranglers told us that a long, long time ago, but it didn’t really. The thing I’ve been writing lately has gone on hold a bit, thanks to Vladimir Putin. It was about something else that happened in 1945, when an American airman missed the last transport back from a dance in Ipswich and had to walk back to his base at Leiston, 22 miles away. He had to fly his unit’s last combat mission of the war the next morning. I doubted it could be done so I walked it myself.

The problem is, my proofreading friend was wrong. It is relevant. Everything about Russia invading Ukraine is about The War, and specifically how Roosevelt and Stalin carved-up Europe at Yalta, planning how the world was going to be run. Churchill was remarkably like Prime Minister Johnson it seems, claiming and presumably imagining that his and Britain’s influence was what the world listened to, when it was all but completely irrelevant to how things turned-out in Europe after German forces surrendered.

It’s all happening again, just as pointlessly, just as predictable, with exactly the same bombast and weapons-grade lies from the British government about how Our Brave Boys beat Johnny Ruskie at Crimea and we – oh sorry, chaps, I meant you, I’ll be a bit too busy to be there in the trench – can jolly well do it again.

The same people are losing their homes, the same people who lose them in every war anywhere, ever. It never changes. I don’t know whether that makes a little story about a walk through the dawn 80 years ago relevant or not.