I cycled nine miles to a friend’s farm the other evening to be there for a meeting at seven. We were going to discuss the business plan I’m writing for her, changing her experimental pastoral herd to one that can sustain a modest living for more than just the cows.

It was a sunny, late June evening and the back-from work rush-hour was starting in Butley. There must have been four cars altogether, two behind me and two coming towards me, one of them waiting to turn into the side-road on my left.

It was a little red car, about 15 years old by the P-plate. The woman driving it was a bit tanned, wearing shades with her hair in a top-knot. All the car windows were down and there was music blasting out. I didn’t recognise it at first. You don’t normally hear anything in Butley. When the Butley Oyster was open there used to be old photos on the wall, memories of a time when things ever happened in this tiny, usually silent village. The pub used to be confused with the Butley Oysterage at Orford, four miles away, famous for its food and when people from London phoned to try to book a table, the landlady, who never, ever served food, thought it was terribly clever and amusing to pretend she’d never heard of the Oysterage and that she had no idea what anyone was talking about. We simply roared. Odd that the pub is shut now. But like most of Suffolk, despite what the more moronic inhabitants like to pretend, it hasn’t always been like this at all.

The photos on the wall of the pub proved it. All of them in black and white, faded with time. One of them showed a crashed Heinkel in a field, a wrecked German bomber surrounded by British policemen, civilians and a man in un buttoned RAF tunic, holding a machine-gun from the aircraft at waist-level, pretending to be Jimmy Cagney over 70 years ago. The other photo I always noticed was from the same period, when Suffolk expected to be the front line and over-run. Especially this part of Suffolk. This whole area was off-limits to civilians for most of the war. Whole villages were simply confiscated and everyone told to leave for the duration. Iken was one, where thousands of Allied troops charged up the beaches of the Alde in practice for Normandy. Shingle Street, just a few miles away, was another and to this day, no-one really knows what happened there, nor whether or not there really was a German landing that resulted in hundreds of burned bodies being washed up along the shoreline. The photo showed the local Home Guard unit, the men too old or too young or too infirm for active service, kitted out in their uncomfortable-looking serge uniforms and re-cycled WW1 Lee-Enfield rifles, leftovers from the War to end all Wars.

There are lots of sad things about old photos, not least the fact that in any photo seventy years old, its likely that even the youngest people are actuarially likely to be dead. But there was always another sadness about this photo of the halt and the lame. The Home Guard were by definition the men who couldn’t join the regular Army. The sad thing was the number of them in the photo, more old and young, more men unfit for active service than live in the whole village today.

Suffolk more than many rural places has changed. The communities are fragmented. If you’re young you have to move away because there are no jobs. If you’re old you almost certainly didn’t make your money in the area and want to preserve the picture postcard fantasy that ‘it’s always been like this,’ without inconvenient children playing or teenagers snogging each others faces off in the bus shelter, thank-you very much. Without any motorways and a farcical, un-commutable railway service that means the 97 mile journey to London takes around two and a half hours, once the farms mechanised there simply wasn’t anything for anyone to do. The farms weren’t the bulwark of society people like to pretend. They got rid of the horses and got rid of the men who worked on farms. That got rid of the whole point of most of these villages. The people drifted away, apart from the ones too old to do anything except hang on in the twilight of rural zombie world until the end.

We will not sleep

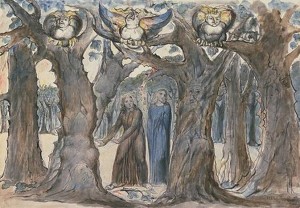

The music was still hammering out of the little red car when I recognised what it was the girl with the top-knot and the shades was listening to somewhat unbelievably: Jerusalem. William Blake wrote the lyrics, one of the weirdest artists and poets who ever lived in the middle of London. I used to walk past where his house had been most days, just round the corner from where Karl Marx lived in a two-room flat writing so passionately about the exploitation of the proletariat that he got his maid pregnant. The song became the anthem of the Labour Party long before Blair re-branded it Tory-Lite (‘I’m Bombin ’ It’™). But it used to mean something, Blake’s Albion, the Labour-landslide 1945 generation’s self-reward for its blood sacrifice twice in what was so obviously not then an average lifetime.

Blake must always have sat uncomfortably with the buttoned-up church folk. Like Dickens, he only once saw a ghost and then one no-one else saw or had ever heard of. He and his wife once sunbathed naked at a time when most decent people didn’t even take their clothes off to wash once a week. And the paintings, the poems about tigers, the rays of sun, the tablets of stone, the amazement and the wonder that radiates from everything this strange man painted and wrote, the power of the imagery and the dark undertow beneath dull little rhymes about diseased roses and flying worms. All of this, belting out of an old Nissan in a country lane one Friday teatime.