There’s a new movie out. In fact, like my revisited reaction to On The Road, the novel, when I saw the 2012 film for the first time the other night, there isn’t. It’s on Channel 4, if you’re interested. And maybe, as I was, you ought to be. It’s about an America that just after the war a group of young-ish people went looking for. Except they weren’t that young, having been you can find out online well out of their teens and for better or worse, having grown-up first in the Great Depression, which affected almost absolutely everybody, and then in the Second World War, which laughably or otherwise after Pearl Harbor charged many Americans with the belief that they had almost a spiritual need, call and duty to save the world, first and foremost by being American and secondly, almost incidentally, by killing Krauts and Japs, much as them pesky Redskins had been in the way of their grandparents’ manifest destiny.

Mommy’s Boy with ishoos has a mahoosive crush on this glamorous waste of space who gives him a free go on his girlfriend and travels across the country with him several times, by car, pickup truck, freight train and hitchhiking. The people they inevitably meet, history being inevitable, as Malcolm Bradbury’s Howard Kirk reminds us all, turn out equally inevitably to be either a) wild crazy hipster cats and proto-Beatniks who know no boundaries; or b) racked with wild and indescribable sadnesses the narrator thinks are the soul of proto-America ( so long as they ain’t Injuns who don’t get a look-in, obviously); or c) both.

The more I watched the movie the more I remembered things from the past, mine and Jack Kerouac’s. I loved this book and the way it changed my life when I was walking the mean streets of Trowbridge on my paper round. It made me go on my own road trip, one I planned for years and finally did, ten years later. It also reminded me how yes, I’d met people like that. And I also remembered I’d learned to avoid total self-absorbed blagging ego-centric arses, but only too slowly. As shop signs about asking for credit used to say, a punch in the mouth often offends, but equally often looking back it would have probably been the right thing to do.

But at thirteen, posting copies of the Bath Evening Chronicle through letterboxes in the gathering dusk on Pitman Avenue, (yes, the shorthand Pitman, he lived in Trowbridge, there’s a plaque about it where that policeman got stabbed) On The Road was a hymn to freedom. Not many years after that I read something written on a barn wall.

“Freedom? Are the sparrows free from the chains of the sky?”

Which for graffiti on a barn full of bits of ancient motorcycles that today would be somebody’s entire and very generous pension fund and then at best was some greasy hippy with a stupid name’s falling-down shed full of rubbish, was a pretty acute observation, then or now. Dean Moriarty’s 1949 Hudson didn’t buy itself. On the truck farm where Sal Paradise met his Mexican – ooops, sorry, Latino – stoop labour girlfriend, if you didn’t work you didn’t get paid and that meant you didn’t eat. Working for a pittance isn’t freedom, as he found out. It was no more real than paying your mortgage off, or getting your book about it published. And it was no more “America” than say, Sergeant York was a typical conscientious objector. The America of Mad Men and Wall Street, let alone Breaking Bad and 24 didn’t even exist in America back when Kerouac rode the range. They didn’t have Interstate highways back then. There wasn’t even a proper road when the US Army drove coast to coast in 1919. Aspen – yes, THAT Aspen, Dallas-opening-credits Aspen – didn’t have tarmac on its Main street until 1960.

But I didn’t know all that on Elmdale, Blair and Eastview, bringing the evening news about Chilean refugees to the good folk of West Wiltshire, first on my rubbish scrap bike then when I was 14, on my lime green metal flake Carlton Continental, £40 on installments to my mother, when £40 was a pretty big deal. What I thought was a pretty big deal by then was Hunter S. Thompson.

For our younger readers, HST was a man who wrote stuff. What he wanted to write was The Great American Novel, so after he was kicked out of the US Airforce, for many of the reasons Kerouac was kicked out of the US Navy, he went off to Big Sur and wrote in the place where Kerouac visited while Thompson was doing odd jobs, where Hemingway shot himself and Richard Brautigan did the same. Maybe it was something in the water. Or maybe it was because all of them were regularly off their face. Either way, Thompson learned that however much he got off his own face absolutely nobody wanted to publish his fiction, although ultimately that’s exactly what happened in a way he didn’t predict.

In San Francisco at the dawn of the 1960s he bought a Triumph motorcycle and rode around with the Hell’s Angels, always something of a high-risk hobby and one that ended the way a six year-old might predict. He wrote what I’ve always thought the best sociological study of a marginalised group I’ve ever read, the not-very-originally-titled Hells Angels: the Strange And Terrible Saga Of The Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, which absolutely no Sociology lecturer I ever met at the University of Bath ever felt necessary to discuss or even acknowledge it existed.

The paralysing straightjacket of the legend Thompson became holds that he was way out there on the edge, feeling no fear. If you watch his post-being-beaten-up-by-them televised encounter with one of the Angels he used to hang around with, you’ll see for yourself what a crock that was.

But I didn’t know that either, back then. All I wanted to do was go to America and meet Hunter Thompson, then make a living writing like him. I did half of that.

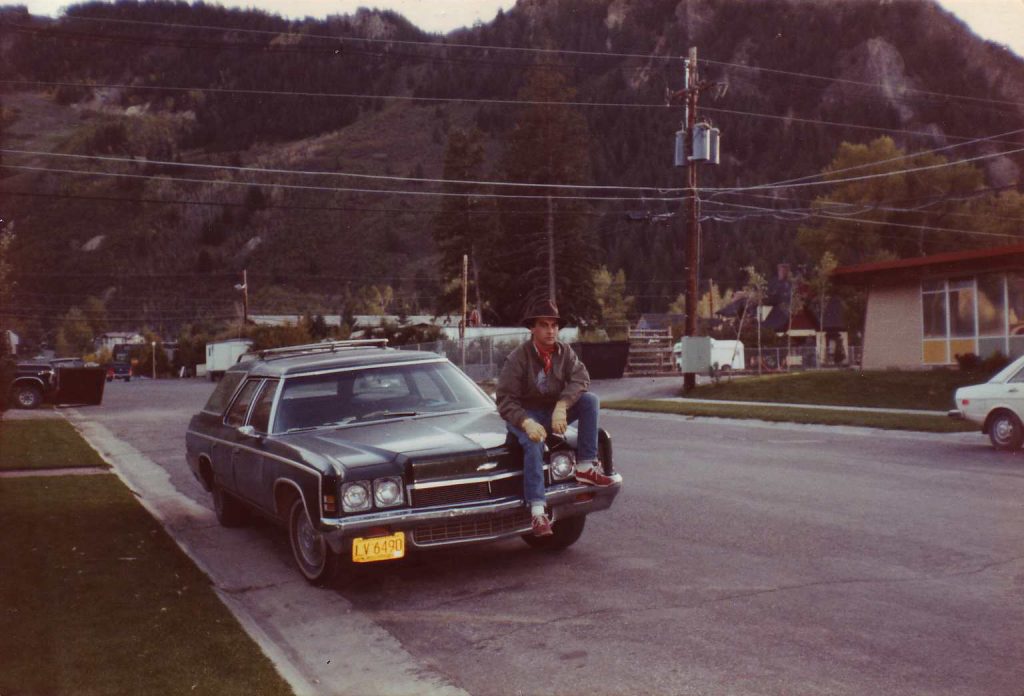

I got the opportunity in the early 1980s to go to teach kids to shoot on a summer camp in Wisconsin. I found several things there; guns, cheerleaders called Nancy-Jean, a lake we parked by in the best Meatloaf tradition. I also found a Chevrolet Kingswood, a laughably massive estate car that did nine to the gallon around any town and a thrifty fifteen on the open road. Apart from the time I drove up over the Rockies, stopped for a break and when I tested the new puddle on the road below the exhaust pipe, when it seemed to be blowing petrol stright through, unburned. That was a Kerouac day, getting clean in a creek next to the road, seeing my big toenail turn the same colour as my jeans and only discovering later the water was so cold because it was glacier run-off; blowing a cooling hose on the plateau southeast of Buena Vista and getting a lift from a truckload of Latino migrant workers to a garage open on a Sunday that sold me a top hose for 82 cents. Like the dog named Boo, a screwdriver, a Jubilee clip and another tank of gas and we were back on the road again.

Was it worth watching? Yes. For me, anyway. Was it worth doing it, any of it? Kerouac’s road trip, Thompson’s desert run to Vegas, my own, more pedestrian meandering from Eagle River to Greencastle to Terre Haute, through tiny river towns of Missouri to St Louis guided by the Rand-McNally and stopping at gunshops – the easiest place to talk to strangers if you spoke the language, and thanks to shooting at Bisley and a summer of teaching it, I did, back then. After an abortive Saturday spent first driving through an electric storm, then in definitively the worst bar I’ve ever been in in my entire life, a barn of a place in Colby, KS, where everyone was carded on the door and bar staff wore Mace canisters on their belts I headed southwest towards Colorado Springs and then up over the first ridge of the Rockies.

On the last day of August I drove down Independence Pass into Aspen and my life changed. I don’t think it ever went back to how it had been before, but anyone can say that about pretty much any day they care to name, if they can remember it at all. There were some serious things wrong with the place, like oh, I don’t know, Goldie Hawn not looking like Private Benjamin when she went to the thrift store (no she didn’t and yes she did, respectively), Andy Williams reportedly buying-off the police investigation when someone got themselves shot dead in very odd circumstances, someone else deciding to sort-out who was going to bed with who with an AR-15 one dark night on a quiet backwoods track, or the dealer guy who got into his Jeep one fine day, turned the key and didn’t have time to even sing man, that’s all she wrote when it exploded. But hey, nobody ever said Aspen was perfect. It just pretty much was, a place of sun and snow and good-looking people and what looked like open-ness, a place where the dustman’s dollar was as good as John Denver’s in any restaurant. Cash, obviously.

Fat City

I tracked HST down to his house outside the city eventually. It took a little while, not least because some people thought I was a cop or someone serving a warrant and some just didn’t like him or the attention he brought to the town. He stood for Sherrif in the early 1970s and at least according to him, came within a spit of getting elected. One of the things he proposed still makes sense, renaming Aspen officially as Fat City. That way the people who just wanted to live somewhere quiet and beautiful, or the people who wanted to play music or listen to it instead of being seen going to listen to it, or the people who just wanted to be left alone to ski could get on and do that. Meanwhile the shopping malls and developers and people selling $200 T-shirts would have a hard time getting start-up funding for the Fat City Apres-Skiwear Boutique or Fat City Jetplane Concierge LLC. You can see the problem.

Thompson got himself arrested for sexual assault around about that time, which took the edge off wanting to be like him, for me at least. Last time I saw him was standing alone on West Hyman, very tall and balding in the sunlight, absorbed in something I’d now say was a mobile phone message, but couldn’t have been back then. I never knew what it was. But by then I didn’t care that much what he did. Nor, to be honest, what Kerouac did. I had my own things to do. I just wish I could have done them in that golden place on the Western slope of the Rockies a lifetime longer. Just like paradise by the dashboard light, it was long ago and it was far away. Still, as Bruce Springsteen told me personally, nothing we can say or do is going to change anything now.