It was probably today, but it might have been Friday. Either way it was a long time ago and Easter. I realised years ago that there was something wrong with my hearing. I’d get things wrong, not understand what people said they’d said, be accused of not listening when in fact I was listening as best I could. But the day like today, the day I’m thinking of at Easter all that time ago, it was the silence that was the loudest thing.

It wasn’t a religious experience, or maybe it was. Back in that Easter long ago I’d gone to my school with my friend Phil. We kept two Enterprise dinghies in winter storage under the parquet floor of the solid municipal 1930s assembly room in what had been the old Girls School before the co-ed revolution. The only reason Phil and I were there was to paint the boats for the new season. It took most of the day, a lot longer than we thought it would, to sand them down in a world when 17-year-olds didn’t have power sanders. But then, we didn’t have the right colour paint either, or not the colour we’d thought we were buying.

We spent all that time working on those boats and talking about the girls we knew and our plans, our huge teenage plans, although mostly those involved the desperate difficulty of finding a venue and then possibly less difficult, removing the clothing from those same girls rather than anything more long-term advantageous or profound. I remember that day a lot though, and I remember the silence we had as well, just working together on something we wanted to do, as well as the talk about the other thing we wanted to do. We got the boats painted, at least.

I had a brilliant Easter this year. Walking around Norwich on Friday, exploring Beccles on Saturday, then trying to find breakfast on Sunday, finding the Common Room in Framlingham closed, finding we didn’t want breakfast at The Crown, driving to Aldeburgh and fish and chips there, then realising I’d left my scarf in Framlingham and having to drive all the way back there, then a glass of wine at the Easton White Horse, then a junk shop where I bought a tyre iron and on to Seckford Hall, a secret place we found where for the price of a pot of tea you can pretend Enid Blyton will be along any minute now and you really do live in the style of Downton Abbey every day. It was good in the end, but a bit unsettling and 8 hours is a long time to spend going out for breakfast. It was gone six by the time we got back, the day the clocks sprang forward. Best beloved went to make a headstart on her accounts, I went shooting.

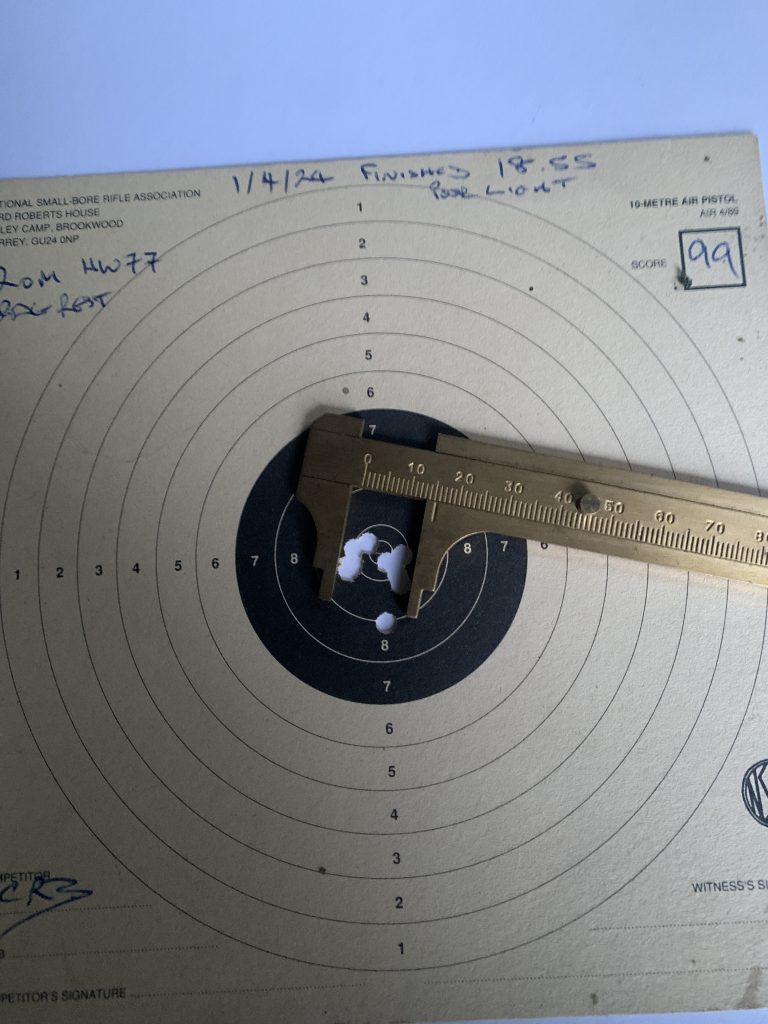

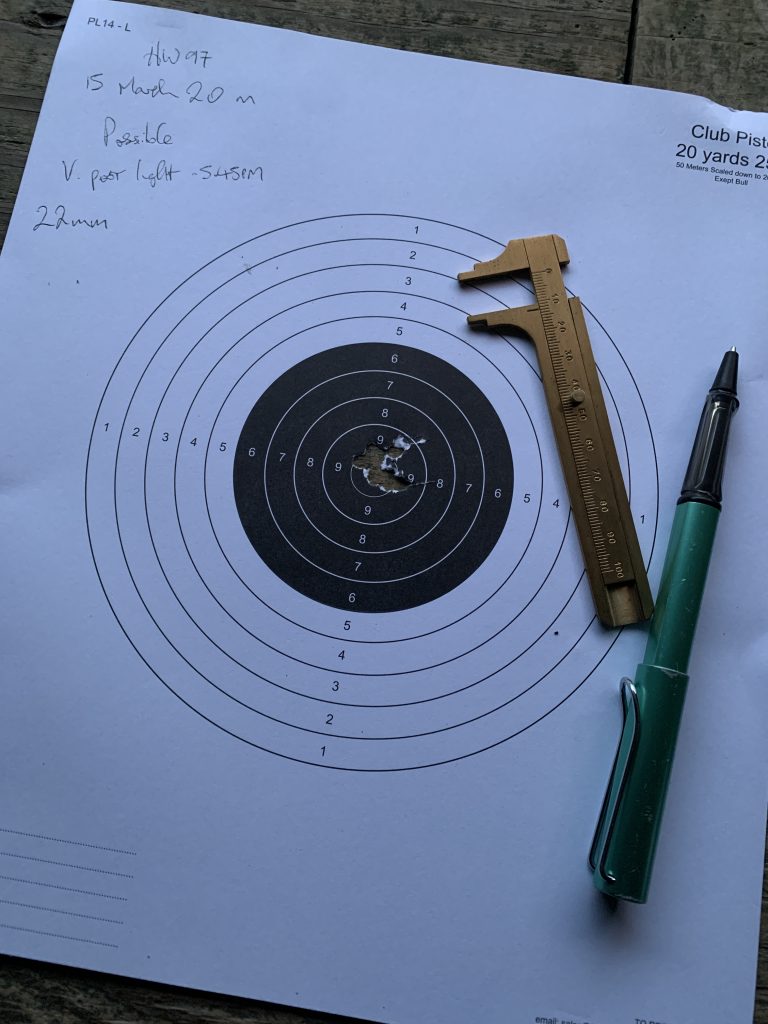

It was ok, considering the light was going and I was having to re-focus the scope to get a clear sight-picture every few shots by the last target, which was this one, a decent card apart from the one stupid flyer.

The range I shoot at is walking distance from where I live, so that’s what I did, walk there. I left the target rest in the boot of my car and just took my best rifle and a bag of ear defenders, ammunition, my sighting target, a pen and a bronze caliper to measure the size of the group of ten shots.

Then I walked back, gone seven in the evening, the few birds singing, the air still. But what I noticed most was the silence as I walked along the lane, the same sound I’d heard that other Easter, at the other end of the span of my life.