I’m not a historian. I don’t know the reasons people do things, except that sometimes they do things for reasons they don’t quite know themselves; for reasons they don’t acknowledge; for reasons they say. And sometimes just because. Because everyone else is doing it. Because it seemed like the right thing to do.

He was born in Texas but went to school in Iowa. His grandfather rode a horse up there from Texas and it took two weeks. His father took a train up there too; that took two days. In the 1940s Joe flew a jet the same distance in about two hours.

He was a pilot. He was a short, slight boy whose family had been doing pretty well with their jewellery store, putting every present you could wish for under the tree at Christmas until the Great Depression. Then there was pretty much nothing. And the small, short boy wasn’t Mr Popular any more.

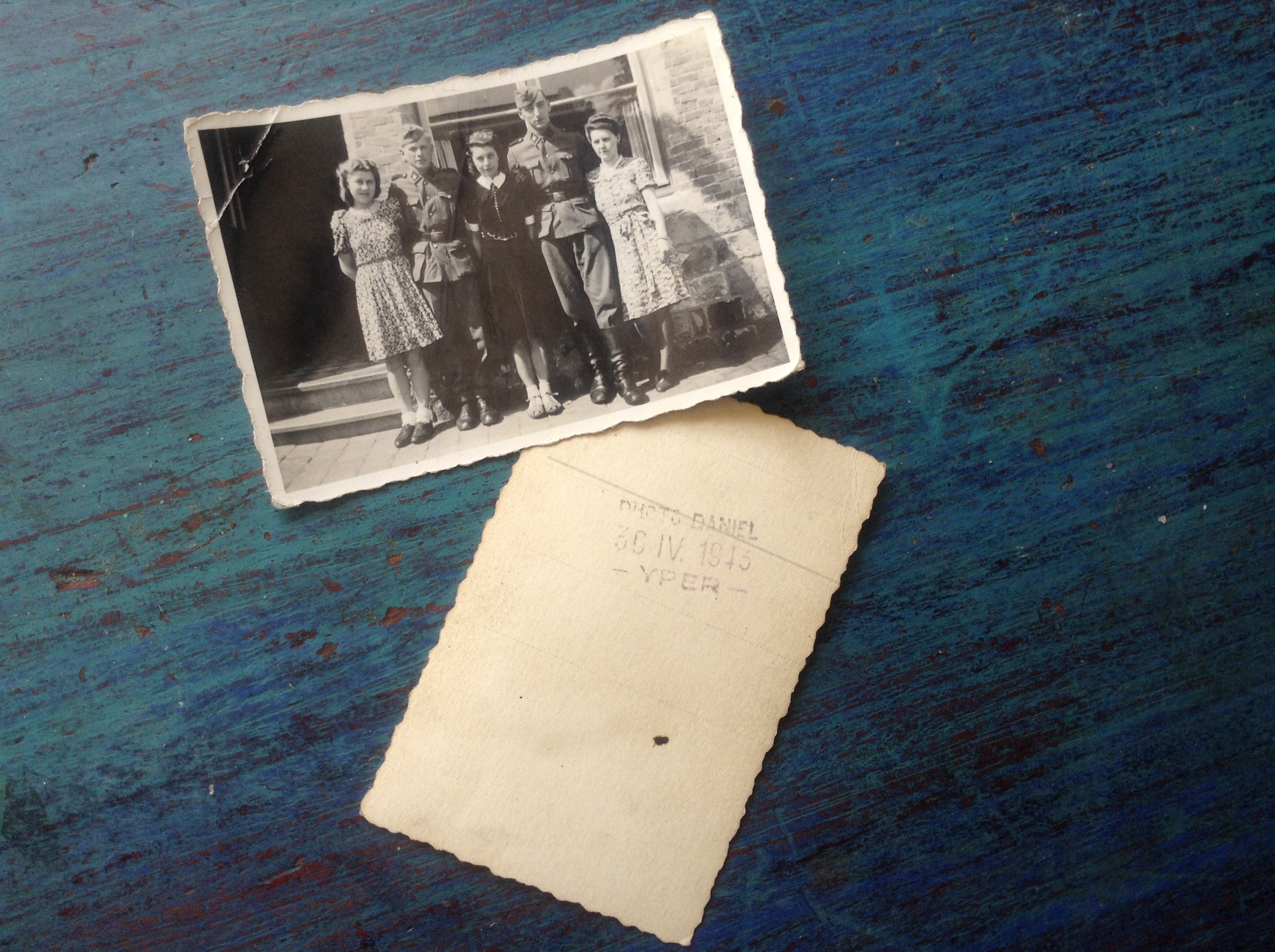

When Pearl Harbour happened in 1941 he told people he wanted to be a pilot. He told me most folk laughed their asses off at that idea. But he did it. He got to England in January 1945, on a ship that had to hang around off Le Havre waiting for a U-Boat to be dealt with before landing in England; the airplane he hadn’t yet seen went to Liverpool, like every other P51D Mustang. He told me that when he went to the airpark there with a buddy it was dangerous just walking down the street, two US pilots in uniform and what seemed like thousands of women whose husbands, partners, lovers, sons had gone to the war.

I met him in 2006. He stayed at my house for ten days or so in 2009 and again in 2011, visiting England for the memorial service the Friends of Leiston Airfield held every May. He kept his room spotless and silent, so much so that one morning we were convinced he’d died in his sleep after a long night drinking and flying World War Two over Germany and Czechoslovakia. It opened my eyes. All I knew about military flying back then was based on Biggles and David Niven, 633 Squadron, the Dambusters, Twelve O’Clock High, The Night My Number Came Up and all the other plucky stiff-upper-lip Johnny Head In Air propaganda, where dashing American officer Gregory Peck always cops off with the local squire’s daughter and gets billeted in a house half the size of Kent. Joe told me it was a big day when they got a second stove to heat their eight-man wooden hut.

He told me other things too. The story of a local Suffolk girl he should have married, a girl he left behind when his squadron was sent to Germany. About the one and only time he dated a German girl there, and how when he kissed her gutten nacht someone emptied a magazine full of 9mm at him from a machine pistol when all he had was his service issue Colt, a nearby wood and fast legs. He told me about friends who died and friends who lived. He told me how the weather had changed from fog more days than not, winter into spring of 1945 and how we worked out together that it wasn’t fog, but coal fires. It’s hardly ever foggy here now.

And odder, darker things. He told me early one morning, drinking grappa at 2am, about a friend who couldn’t keep his airplane straight in a dive, practice bombing on the river Orwell; how his wings had folded back and come clean off. About friends who took off in a flight of three, pulled up through the clouds and found there were only two airplanes that came out of the top; the same thing happening to others setting-down through the cloud, with the North Sea waiting below. the flying over the coast coming home, looking for the river running parallel to the sea at Aldeburgh, flying up the coast from there until he found a radio tower at Minsmere, turning 210 degrees on the tower which would put you at the end of the main runway at Leiston, then putting-down through fog, cutting the engine at 50 feet over the place where two hedges met and hoping nobody had parked-up a jeep on the runway. It wouldn’t hurt for very long, he said.

He told me how the weather had killed more of his buddies than the Luftwaffe ever did. He told me about having to fly eight-hour missions, escorting thousand bomber raids, the escorts so much faster than the bombers that they had to cross and re-cross the bomber stream and its ten mile vapour trails every few minutes in flights of four, the inside aircraft having to throttle way back and turn tight while the outside aircraft had to speed up and turn on the outside of the finger formation, then a few minutes later the same thing again, the other way around. Over and again, all the way to the target. He told me about B24s, Liberator bombers, which had a nasty habit of exploding when their bomb doors opened; and sitting, five miles high, watching the ten men inside fall to the ground.

And once, way deep into the bottle, when I said I wasn’t clear what happened in that story, he was almost across the table at me, angry, in my face, spitting ‘What do you mean? You were there.” And I wondered at that moment, not just who he thought I was from that time, but whether for a moment somehow I was, for him. Whether we’d called-up something that shouldn’t have been called after so long sleeping. The same thing happened to an American friend way back, visiting an abandoned 8th Airforce airfield one wet and boring Sunday afternoon, wearing an American leather flying jacket. He ordered his girlfriend a drink and almost choked on his own when an old man at the bar in an almost empty, strange pub in the middle of nowhere looked hard at him and said simply, ‘You’re back, then.”

Joe Shea never shot anyone down, although he tried. He left the US Air Force after the war, went home and built a bathroom onto his parents’ house. Then things went a little sour. He told me that little guy had been nothing in that little town outside the airforce; he’d gone back, he said, to being nothing there again, so he re-enlisted. He stayed in the Air Force all the way to being Lt.Colonel, although he hated being called that. I never knew why. He was part of the team that had to find the atom bomb the USAF lost after a plane crash in Spain, wondering if they’d ever find it or whether someone knew exactly where it was while they looked.

And he told me about a time when his airplane just wasn’t making enough power taking off at Leiston airfleld, just down the road from where I sit on the edge of another Suffolk airfield. He switched off, ran over to a spare Mustang on the flight line and borrowed that to fly the mission. Except he was in a hurry to keep-up with everyone else taking off. He was short. And the usual pilot wasn’t, so when he powered down the runway his feet didn’t quite push the rudder bar as far to the right as they needed to, to counteract the torque of the engine pulling the airplane off the tarmac onto the wet mud it slewed onto. Slowing down would have meant that the wheels sank into the mud at about 120mph and cartwheeling across the airfield with full petrol tanks. It wouldn’t hurt for long but he kept the throttle open, the only thing that seemed sensible in that split second. He went straight through a hedge a few inches off the ground. There is still an airplane-sized gap in that hedgerow today.

On July 4th 2004 another Mustang went the same way in Durango, Colorado; once in the air the torque flipped it upside down. That one crashed. Joe’s machine inverted and he had the luck to push the control column instead of pulling it.

He nearly clipped the roof of one of the hangers before he finally, sweating, heart in mouth got the machine pointing the right way up and under control. The control tower laconically told him “You can put your wheels up now, Joe.”

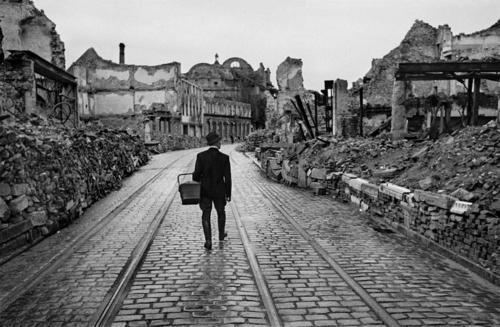

His life for the past twenty years wasn’t easy. For a number of reasons he had to keep working and like anyone his age, while they say time loves a hero, illness and disease loves time, especially when it comes to human bodies and their frailties. Joe Shea died this year, one of a generation whose motivations and drivers, whose strength and resolve I can’t entirely fathom from here. He was not, he said, a hero. He did some things in that aircraft that didn’t help to win any war, that killed people who had done nothing to deserve killing. As people do in every war.

He could be abrasive, demanding and dismissive; he refused to help an old man in Yoxford re-visit a place where a young friend had blown himself up playing with a bomb dump by the side of the road. Apparently there were munitions dumps everywhere. He flatly refused to talk to a re-enactor who had spent thousands on a USAAF Military Police uniform at one memorial service; he told me he’d spent his war avoiding MPs and goosing his airplane up behind them riding motorcycles as they lead the Mustangs along the perimeter track around the airfield, so why the hell would he want to talk to someone pretending to be one now?

We drove him around some of the old sights he’d seen and helped him get some old pictures back home to a museum in America. We gave him a lot to drink and he told us stories he said he’d never shared with anyone before. Then we lost touch, moved house and life went on, the way it does. The way it’s supposed to. He died in his 90s. He felt bad for a long, long time, about the beauty of the colours of a German aircraft exploding in mid-air, this same man who when he saw a book cover with a photo of a crippled Me 110 said calmly it was on the correct course:

“Straight down into the ground with smoke coming out of it.”

In a little lane near Leiston there’s a concrete memorial to the eighty-two pilots who died while they were stationed at the airfield there. An inscription on it is from the King James Bible, the one I always thought was the one true text not as a zealot but because I didn’t know any better, which is maybe the same definition.

Proverbs 23:5

They fly away as an eagle toward heaven.

Who knows? Maybe they did. I remember the fear and the shame and the horror in his voice when he described the beauty of the colour of another man’s life exploding in front of his eighteen year-old eyes, two miles up in the sky. I hope he found peace.

A long time ago a man in uniform said what I hope is true now, the way it was that wet, nearly final day in Spring, 1945 in a Suffolk field.

You can put your wheels up now, Joe.

When J.M. Barrie’s play Peter Pan first came out, grown men left the theatre sobbing. Not because it was rubbish and they’d been pulled away from an agreeable evening at the club to go and watch it with a wife they rarely saw, but because of the central theme. Peter’s merry band of boys weren’t all that merry. Like him, they’d never grown up because they lived in Neverland. They’d been sent to schools that ripped them away from their families. The part of them that would have grown in a family was lost forever. That part of them was dead.

When J.M. Barrie’s play Peter Pan first came out, grown men left the theatre sobbing. Not because it was rubbish and they’d been pulled away from an agreeable evening at the club to go and watch it with a wife they rarely saw, but because of the central theme. Peter’s merry band of boys weren’t all that merry. Like him, they’d never grown up because they lived in Neverland. They’d been sent to schools that ripped them away from their families. The part of them that would have grown in a family was lost forever. That part of them was dead.