Once upon a time, I thought I knew things. Now I think I never will. And that quite often, actually knowing things isn’t what’s wanted at all.

It happened writing Hereward. Charles Kingsley, the Victorian author of the Water Babies (a hundred plus years before Martin Amis wrote Dead Babies, but Kingsley could usefully have borrowed the title save for the fact that nobody then would have bought it, most families being knee-deep in them) wrote Hereward’s story up as The Last Englishman. You can see the tabloid headlines:

Plucky Brit Brexit Rebel Defies Normans

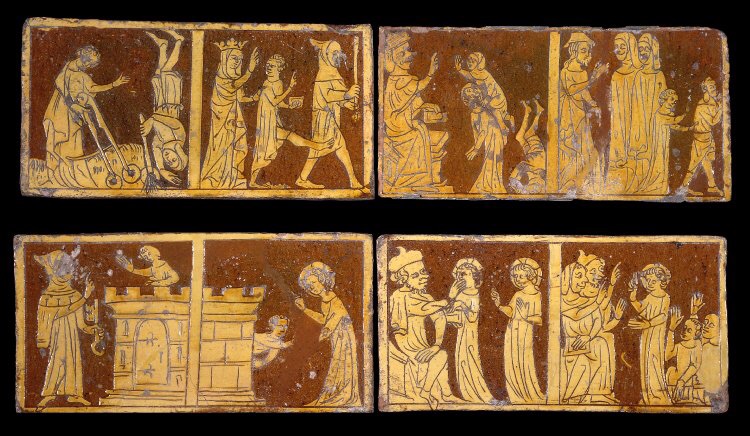

Except Hereward wasn’t the fantastic Pure Brit of racist fiction. Because there’s no such thing. He was a Saxon, whose people came from Denmark, Holland and Germany, which is why it’s called Saxony, which is near where the Queen’s family come from too.The Normans came from Normandy, but not even a hundred years before that, they came from Denmark too.

Chin up, fantasists. I’m sorry if this is news to some of you. Big boys don’t cry.

Hereward’s cousin was the King of Denmark, one of the Sweynes. One of the more confusing thing about writing about those times was the appalling shortage of names they seemed to have. If you weren’t called Leofric then Sweyne was pretty much compulsory, unless you went down the Aelf-suffix route. From the Other World, the land of faery. Yes, as in Aelf Garnett. Satire doesn’t change.

On Sunday I started writing Double Vision, based on the tale of Rudolf Hess.

How about this for a fiction plot?

It’s 1941. The British Army has been hammered at Dunkirk, the year before. Get your flags out, because plucky Britain Stands Alone. America’s not in the war yet because it didn’t suit it. Russia’s still best mates with Germany, or thinks it is. Hitler’s deputy steals an airplane. He flies a rectangular course over the North Sea for no clear reason and seems quite proud of this in his interrogations.

He eventually parachutes out to land a little south of Glasgow in Scotland. He announces he’s called Captain Albert Horn and he wants to see the Duke of Hamilton. He has the idea that the Duke (serving in the RAF quite nearby) will talk to people like Lord Halifax who will lever Churchill and the King into peace negotiations.

He’s bundled off to Trent Park interrogation centre, then the Tower of London and finds himself in the dock at Nuremberg with something of an uncertain future.

For reasons unclear, a spitting-furious Hitler doesn’t hunt down and kill Hess’s family, which he could have done in half a breath. As he threatened to do to Goering’s family, when Goering asked if it was ok to carry out the order Hitler had given him previously.

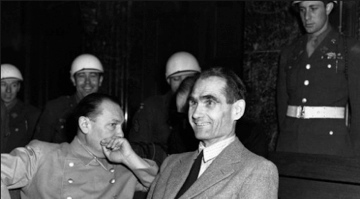

Hess refuses to speak in his own defence. The Allies hang most of the people in the dock. But not Rudolf Hess, architect of the final solution. He didn’t recognise someone he worked with daily. He refuses to see anyone in his family for 20 years.

He claims he has stomach aches. Herman Goerring (head of the Luftwaffe, sentenced to death) falls about laughing at Hess in court. His wife notes that his voice has got deeper in 20 years, when the opposite is normally what happens. Everyone else in Spandau Prison is let out in 1966. Not Hess. He’s the only inmate there for another 22 years.

During this time a British army doctor treating him claims the patient’s medical records don’t match the historical record of what happened to the Rudolf Hess who was shot through the lung in 1916.

It’s not the first time that someone has said that the Rudolf Hess at the Nuremberg trial isn’t the same Rudolf Hess who sat next to Hitler. Goerring sat next to him and said it first, in court:

“Hess? Which Hess? The Hess you have here? Our Hess? Your Hess?”

Eventually a 93 year old man who couldn’t move his arms higher than level with his shoulders ties a noose with electric cord and hangs himself from a window catch 1.4 metres above the ground.

A British nurse who arrived to find the body said that she wasn’t the first person there. She gave that honour to two people she was very specific in saying were dressed like American soldiers. She did not say that they were.

Except it’s not a fiction plot. We’re told that’s exactly what happened, with no logical inconsistencies whatsoever.

I don’t know what happened, or who he was, or whether he went insane, or whether it wasn’t him at all. But I’m finding out I don’t know. I think it’s important.