There’s this film. It’s a story about a murder, an exploration, a road-trip from Londond to Bristol and out beyond, to the sea. A story about boredom and factories and despite it having ended 34 years earlier, this is a story about the war for which England had clearly, for all its lights and industry, not really fully recovered, inside or out.

A story where a multi-millionaire pop star pretends for reasons of his own to be an Eddie Cochran fan playing guitar in a caravan, working in his dad’s garage somewhere way down the A4 that’s gone now, the same way the Driver’s old Rover car is gone now; the same way Utility furniture and big factories are gone now, along with the M4 Junction 2 skyline, even as far out as Windsor; the way telephones with dials and cords and big black and white televisions and rooms without central heating are gone now.

That was the world I grea up in. That was the world I expected to live in. And while lots of things are better, like not being cold all winter, a lot of it I miss in a way I don’t often think about, but the ache is still there, like an old tennis injury. Or a psychic scar.

Radio On has a simple story. A man is found dead in his bath. One of his last acts was to send his brother three Kraftwerk cassettes for his birthday and beleive me, that would have been a pretty big present. The brother works, until he walks out of the job, as a radio DJ in a factory on the Great West Road, an in -house radio host lost in the kind of job that has gone now too, the kind of job some of us thought would be pretty cool; the kind of job that couldn’t now even vaguely possibly sustain a rented flat in Hammersmith. It did then. And also the sort of job that left the DJ bored and numb. Or maybe that was just the death of his brother.

We walks away, or rather drives away, to find….well, it isn’t made clear. A short haircut when that was pretty revolutionary in itself. Bristol. The cause of his brother’s death. The revolution, by way of Astrid Proll, the Red Army Faction and a new German maybe girlfriend, because the old one reckons he’s doing her head in with all his stuff.

The literally Dickensian decay of pretty much everything around oddly doesn’t clash with the music that to me at least, sounds new and now. The quaint old cars, the cold, the decision to shoot the film in black and white, the decision to shoot the film at all when it was so much of a non-road trip, down the M4, come off at Theale, pretty much the way I used to run that road, not crossing the M25 because there was no M25 to cross, off onto the A4, the old road of shepherds and stagecoaches and Johny Morris’s son’s pub, the Pelican. And snow that winter. I remember that too. The smell of the cold. The feel of its teeth in the bones of my arm.

And good contrasts. The jukebox left over from an imaginary benevolent USA blasts out “I saw the whole wide world’ as the Driver looks out of the bleak windows of an almost empty pub somewhere outside Newbury. The 1950s Rover rolls sedately along near Heathrow while a Jumbo jet soars into the future at the end of the bonnet. Except it doesn’t look like the future, this vision of England’s glory. Like the future, there didn’t seem to be one, back then.

And Ireland. And the Provos. And Bader-Meinhof. And squaddies hitch-hikinbg and spilling thier PTSD fallout stories, the same ones I’d heard of corss-border firefights, smashing down a flat’s front wall with a Browning .50 calibre, stories that never, ever made the papers because the papers, then as now, lied to give a one-sided story. We just didn’t know they did. We didn’t beleive they did, anyway. All of this airbrushed out of history now by the same papers, so we know that all terrorists are and always have been Moslems because it suits the government and its sponsors for us to think that.

These garages, these farms seen through the windscreen, the blue remembered thrills, the same farms and garages of lost discontent I saw through my own windscreen, out past Silbury Hill. And does any of this matter?

These cars, these phones, those demons are dead. Aren’t they? Cars always start these days. Nobody’s even seen a starting handle, nor a Rover P4 if they’re under 40, or Sting hamming it up in a caravan outside Hungerford, nor a garage where a man comes out to pump your petrol for you.

The Driver asks Sting: “Are you going places?”

Of course not.

This is all old stuff. I should leave it where it lay. We’ve all got new phones. But I can’t forget David Bowie stopped singing Heroes and asked us a question instead. Where Are We Now?

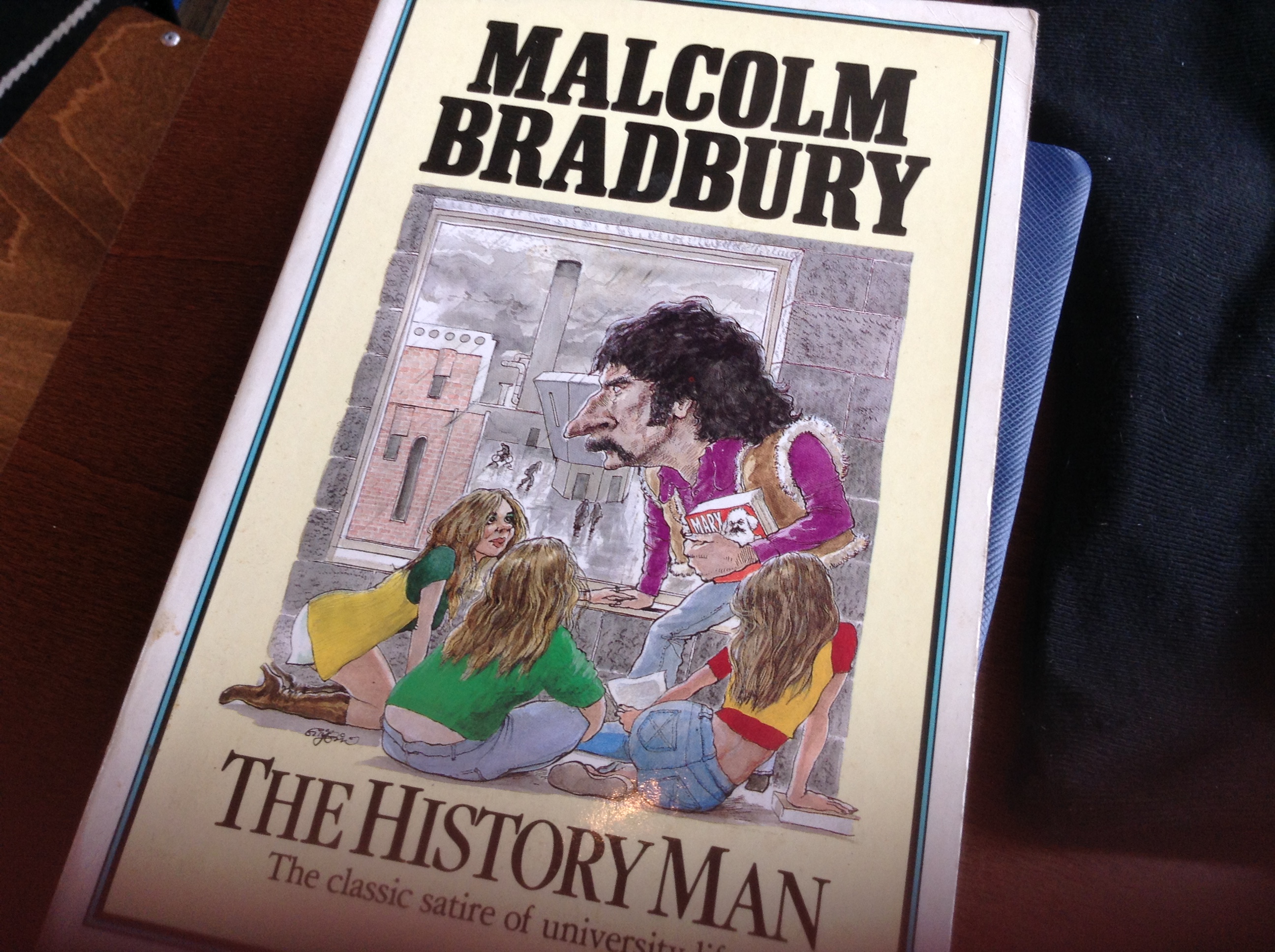

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties.

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties.