On Friday, without changing the subject, I got out of work early enough to stop in Woodbridge on the way home. I was looking for some mussels for dinner but somehow never got to the fish shop and by the time I would have done I’d found what I was really looking for anyway. Down a little alley, next to a deli and a bulding society and an upper floor flat that’s been for rent for I can’t remember how long, according to the sign in the window, there was a church hall.

There still is, but that’s not the point. It had a sign outside with two fatal words on it:

Book Sale

For anyone pretending to be civlised, there’s no choice but to go in. Because apart from books, some of which you’ll want, for pennies, you’ll get a glimpse of a life of if not quiet desperation then certainly one that careers masters don’t encourage. The life of the church hall bookseller.

I found a Cormac McCarthy I didn’t know existed (Outer Dark, since you ask. About incest. It’s Suffolk, after all). A history of the English Civil War, which I embarassingly know next to nothing about, aside from the liturgic Edghehill, Prince Rupert, New Model Army, Naseby, which hardly seems adequate. A magisterial account of the Dunkirk evacuation, where a friend’s father spent a solid week in the water at the end of a human pier, before being rescued and not by anyone looking remotely like Jenny Agutter. A book about the last days of WWII, after Hitler was dead, a time that fascinates me, for reasons I don’t fully understand. I think most of all I have the hugest admiration for people who literally had nothing left, who unlike the British, managed to parlay that into a scuccesful economdy within 5 years. And before any rabid Brexit tries the ‘ah yes, but they got a Marshall. Plan bailout, true, they did. And Britain got a factually much bigger one, and spent it on works outings, chips and a massive investment in cloth caps to tug. /in fact of course, Britain chose to bankrupt itself continuining to pretend it was a world power, first squandering its reputation on Aden and squandering its cash on thermonuclear weaponry, a programme so spectacularly rubbish that it ended up buying American anyway.

I would say I digress, but I don’t. Because the other thing I got at the book sale, apart from a chat with the guy who has read more than 95% of all graduates anywhere, because he does little else, manning the cash box, was a DVD. Yes, I know, how quaint. When you can explain how I can buy a second-hand streamed film I’ll listen.

The thing for me about book sales isn’t just the feeling that life outside has stopped, and there can be days when that’s a bad feeling indeed. It’s the idea that you don’t have to risk huge amounts on books you’ve never read or films you’ve never even heard of. And I’d never heard of People On Sunday. Ever.

Maybe it was because everyone in it died years ago. Or because it was a German silent film made in 1929, or all of those reasons and more. I bought it to learn about telling a story without words. Nobody spoke. Or they did, but you can’t hear them. They were all amateurs. There are about five frames of explanatatory text, but really I don’t think they needed it. Five young people on a Sunday do the things they used to do. I did. They probably still do. Sleep. Get out of the city. Listen to music. Try to cop off with each other in a half-hearted way. Find something a bit more challenging when they succeed.

It’s a moving film. It opens at Bahnhof Zoo and instantly you know something they didn’t. The whole place was going to be flattened. Anyone left there was going to be caught between mass-raping Russians and devoted Nazi death squads acting out thier own personal Gotterdamerung. Hardly a brick would be left. And watching this, none of them know it.

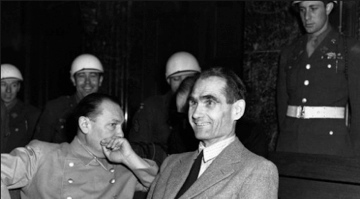

They knew it soon. Most of the people in the film got out of Germany soon after. Thier biographies read like the midcentury itself:

Erwin Splettstößer (de) Himself (taxi driver) – The five leading actors were all amateur actors. He liked acting and appeared later in small roles in two other films also directed by Robert Siodmak: Abschied (1930) and Voruntersuchung. In an unfortunate accident, he was run over by his own taxi in 1931 and died.

Brigitte Borchert (de) as Herself (record seller) – Like her film figure, Brigitte Borchert (born 1910) also worked as a Gramophone seller when she was discovered for this film. It was her only film, she later married the illustrator Wilhelm M. Busch in 1936. She died in Hamburg-Blankenese in August 2011, aged 100.

Wolfgang von Waltershausen as Himself (wine seller) – Born in 1900 into a wealthy family in Bavaria, he was a descendant of Georg Friedrich Sartorius. Waltershausen later had small roles in two other movies. During the Third Reich he worked in the mining industry, in post-war-Germany he sold books and audiocassettes. He was married twice and died in 1973.

Christl Ehlers as Herself (an extra in films) – Born 1910, the daughter of an harpsichordist and an artist. left Germany in 1933 and you know why. During the Second World War, she lived with her mother in the United States. She had a bit part in the Hollywood movie Escape (1940). She later married and had four more children, in addition to one child from a previous marriage. She worked with her husband in a family-owned aircraft company and also had her own vitamin business. Christina and her husband died in a private plane crash in New Mexico in 1960. All of her children are still living and reside in Northern California.

The one that haunts me most is the last, Annie Schreyer. The model. What became of her? Is she still part of the rubble under the new Bahnhof Zoo? There is no information about Annie Schreyer. Nothing on where or when she was born, nor where she died. Or when, or how, or with who. Just an hour of a girl in her early twenties, modestly but prettily enough dressed in a bathing costume, a skirt, a shirt, a hat, smoking a cigarette in the sun, laughing. Did she get out? Was she part of it? We don’t know anything at all. There is no information about Annie Schreyer. On this night when the dead walk I hope she may tread lightly, this black and white girl.