It was probably the last day of sailing this year yesterday. Frankly, it can’t happen soon enough. Last year was fantastic sailing; four or sometimes even five days a week, sailing after work, sailing deep into November. Some of those later sailing days weren’t so much fun, to be honest, a combination of not having the main sail downhaul tight enough, the idiotic tendency of the Drascombe Lugger to go backwards and/or turn itself round thanks to the mizzen sail and the absence for the most part of my brilliant crew member, who found she had a load of work on and couldn’t spare the time.

High Water was half-twelve at Martlesham, so I was on the water at just after half-past ten. The plan was to go all the way down to Ramsholt or failing that, the Rocks, then back, then boat out and a power wash, then the long slog through the winter of new anti-foul, sorely needed after I tried to get two years out of the winter 2020 application. This winter I want to get everything out of the boat, remove all the interior hull fittings entirely and then repaint the decks. The boat is getting on for fifty years old. It’s very sound, but weed, mud and general being-used has left it looking past its best. But fixable, very fixable if I first have this last sail today.

Except the engine wouldn’t start. Or rather, it started just fine, but it wouldn’t rev and after a minute or so running just above tickover it slowly died. For once the wind was blowing from the west, so I could sail out of the creek. It usually changes enough to get back in two or three hours. Usually. I changed the spark plug for a new one, marvelled that the old one worked at all when I saw the sooty old one but it didn’t make much difference. Whatever it is, it’s not the sparkplug. It still died three quarters of the way through the moorings and the clock was ticking. I untied the jib and pulled the port sheet and we sailed out anyway, centreboard up to go straight across the bends in the creek and save some time. When I finally had time to look at my watch it was 11:20am.

Note to Royal Yachting Association, Sea Scouts or anyone with a boat: Don’t do this. It’s dumb. It’s only safe in fine weather and it takes most of the fun out of sailing.

But I did it anyway, obviously. The plan, such as it was, was get out of the creek, moor to a bouy off Kyson’s Point as usual, sort out the sails, head south down the Deben to the fabled paradise of Ramsholt, failing that the Rocks, failing that go round the island at Waldringfield, all of which looked possible. The wind out in the Deben is usually different to the wind in Martlesham Creek where it was from the West. In the Deben it was blowing from the north. It’s the trees, the hills and the general cussedness of the river, which is why that part is and always has been called Troublesome Reach.

Drascombes don’t sail fast and downwind they sail a lot slower. I saw another boat coming up from Waldringfield; Alex whose grandfather knew Arthur Ransome, in his own modern adaptation, a Deben Lugger, a lug rig and carbon spars. It shifted through the water a lot faster than mine but he was going upsteam, I was going the other way.

The first thing was the main sail wasn’t up, so I lashed the tiller and sorted that, then re-tensioned the downhaul. I’d used some old line I had hanging around. Modern nylon stuff hadn’t worked and now it had been happily absorbing moisture under its cover in October, nor did this stuff. It jammed in the bronze tunnel cleat. It would have to do I thought, but in the end it didn’t. After half an hour the wind had shifted to blow straight up the river from the south, so I was close-hauled into it. And for that you definitely need the downhaul jammed tight. I had to take out to the other side of the river to clear Coprolite Quay, twice. Coprolite, for those who don’t know, is dinosaur poo. When the Victorians discovered it lay in huge quantities under the Suffolk Sandlings it became a huge export industry, sent out by sea, which meant from here. The tide was massive today and I could hardly see the top of the quay. Made of concrete and very, very solid indeed it was something I definitely didn’t want to run into.

I’d changed the mainsheet mid-season because the old one, too thick, kept jamming in the blocks so I swapped that out to use as a mooring warp and substituted some brand-new 8mm slinky braid that slipped through the blocks like a snake. It also slipped through the jamming cleat too, not least because one of them had disintegrated its spring so it didn’t flip closed. I never use the horn cleats Drascombes have because I’ve always thought them an accident looking for somewhere to happen. The only way to use a horn cleat is to loop the line around it, over the end, make a loop, reverse it then drop that over the other end of the horn. It’s neat, with practice it’s quick and it’s tight. It’s also a pain to get undone in a hurry without a knife, which is why on a gusty river with a fickle wind it’s something you don’t even want to think about if you don’t like the idea of being 90 degrees tipped-over. Which I’m too old for.

Because I was pointing too close to the wind progress was slow. We got down into the pool below Coprolite and I looked for a bouy to moor up to so I could sort out the downhaul and generally tidy up. The problem was that every one of them was either a race can or a channel marker. Not one of them had a rope on it, or even a ring to put a rope through. It was time to turn around. I’d planned to go through the New Cut, dug in the 1800s to make the river more manageable for the bigger ships that were coming, with predictable results. The ships kept getting bigger and the New Cut couldn’t make enough of a difference to stop them going somewhere else. I’ve heard all the tales of the old barges carrying grain and everything else down this river to London and how the old boys who sailed them carried on into the 1920s, maybe even the 1950s without engines, but I’ve also thought there’s only one reason anyone would do that; they couldn’t afford an engine.

We turned around and headed up river. Alex was long gone in his carbon StarTrek Lugger and I couldn’t clearly see where the New Cut was in this huge tide. I could see the green hull of Peter Duck, one of Ransome’s boats, clear across where the reedy island usually is and today wasn’t. I didn’t want to get stuck there for twelve hours. A powerboat was coming up behind me and being higher he could see more clearly. He came past to port and I followed him in then turned West towards Peter Duck to pick up one of the mooring buoys there.

It all went less than optimal from there. I changed the spark plug because who doesn’t carry a spare? It made zero difference. Started first pull but wouldn’t rev, then what revs there were just died away to nothing. Ok, I’ll sail it back on jib and mizzen, because frankly I couldn’t be arsed to put the main up again and anyway the wind was getting up now, blowing from the south in the Deben and I didn’t want to be overpowered coming-in to the moorings solo. I had to go pretty much all the way to the end of Troublesome to have enough leeway to turn and go straight up Martlesham Creek, where predictably, the wind was blowing from the West again, straight down the creek at me, with the tide going out as well now. I dropped the sails, got the oars out and rowed. It’s only half a mile.

A Lugger happily fantails into the wind when you’re rowing. Add to that that I can’t see behind me and it all took a while to get back. Good exercise, but I was looking for a pleasant sail instead of a workout.

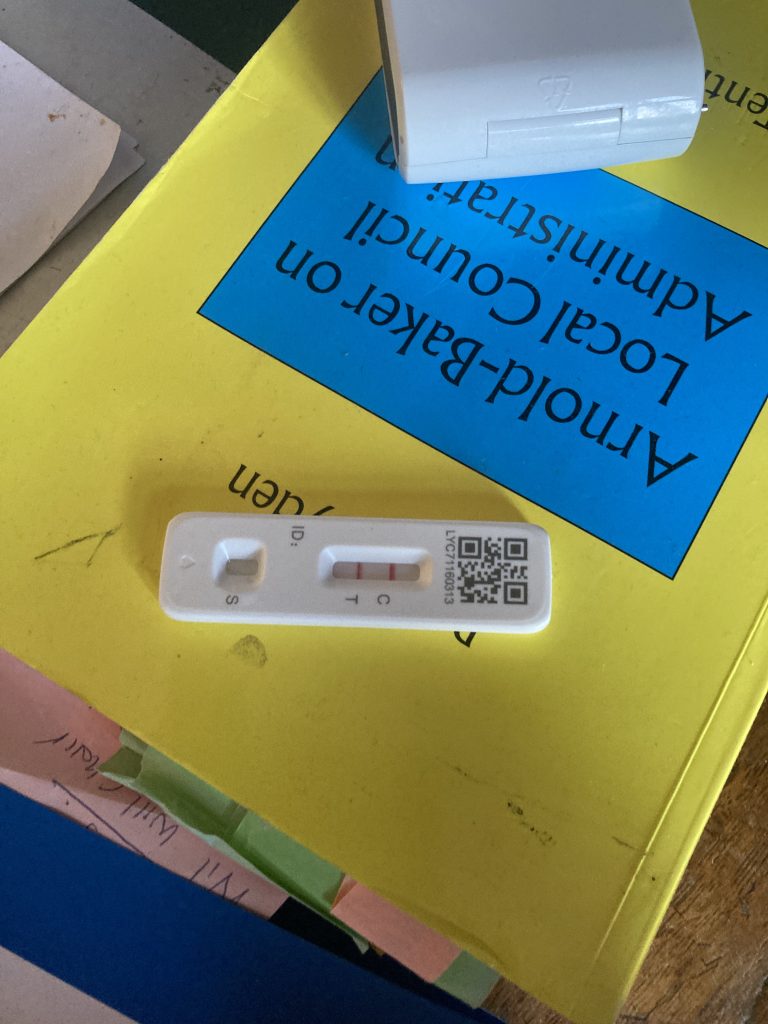

I was out for just over four hours and came away hot, sweaty and not best pleased. I went back today and sorted everything. The engine wouldn’t rev and eventually wouldn’t start because if you look at the picture above, there’s a kink in the fuel line after the fuel filter. Nothing to do with cleaning the filter, blowing through it, dirty petrol, old petrol, bad spark plug, evil spirits, none of that. Just no fuel getting through. A bit of jiggling the line around and it runs fine. While I was there I got rid of the daft German mainsheet arrangement, put a spare block on and attached the other double block directly to the horse. I still need a jammer cleat for the mainsheet, but I know where I can get a nice brass tube cleat that will fit on the tiller arm.

After that pump out the bilge, after that cut some of the nice new red braid line for the downhaul, and that works really well in the brass tube cleat at the base of the mast. Then re-arrange the step fender tied-on at the stern so that if I actually do manage to go overboard singlehanded I stand a chance of being able to get back into the boat.

The last thing was re-tying every line that went around horn cleats, so front and aft mooring warps. I’d watched You Tube and found an absolutely brilliant, quick, safe, fast trick for cleat hitches and horn cleats. The fact I can do it one-handed with my left hand without even thinking and do it much more slowly using my right or both hands is just one of those things. It’s a really seriously good trick.

All in I spent about two and a half hours doing all this today. It was time well-spent. I think I enjoy this stuff more than actually sailing, or certainly sailing on the Deben with its ridiculous wind-shifts. I don’t know if there will be any more sailing this year. The boat’s still in the water if I do but the clocks go back this weekend, the time when I think ‘only six weeks, that’s all you have to cope with, just six weeks and it’ll start getting lighter, you can cope with that.’ And I can. There’ll be another summer on the water. With any luck at all I’ll be there to sail it.