Once upon a time, in a land long ago, there was a thing called the Frome & District Pistol Club. That’s how long ago it was.

I’d learned how to shoot rifles, or .22 rifles at least, at the local TA Centre in the town I grew up in, back in the days when no air conditioning, an underground 25-yard range, canvas-covered kapok mats that Lord Roberts had probably personally specified just after the Boer War and no shortage of adults who would have quite happily clubbed to the floor any kid arsing around with a gun in a nano-second passed for a totally normal Thursday evening in a small town.

I loved it. I wasn’t as good as I wanted to be, and that was the point. I wanted to get better. Slowly, I did. The rifle club sent me to Bisley and somehow at fifteen I shot well enough to get my badge as an adult Marksman, which now I think is just a first and not a great step, but a decent start. I couldn’t afford a decent rifle then, and let it lapse through Sixth Form, but took up shooting again when I went to the University of Bath, and hence the Frome & District. There were other ranges, at Devizes and the weird tunnel range somewhere out towards Radstock in a converted railway cutting under the Mendips. I recall someone shooting a “bullet-proof” vest with a black powder .36 caliber pistol there, to see what happened. It was ok, nobody was wearing it. Except it wouldn’t have been ok, because although on examination the ball hadn’t penetrated the vest, it set fire to it instead, and we had no way of measuring blunt-force trauma.

I shot all through university. When we weren’t doing .22 pistol shooting at our indoor range built in some old quarry scrape we used the Number Two range at the School of Infantry in Warminster, backstopped by the escarpment of Salisbury Plain. That was when I bought my first gun, a .357 Smith & Wesson Model 28. The frame was too big for my hand and more so with rubber Pachmyer grips on what was a heavy brute of a gun designed back in the 1950s for the American police market. I should have bought a six-inch Model 19, but I couldn’t wait. Mr State Trooper, please don’t stop me, as Bruce Springsteen sang.

Maybe you got a nice car. Maybe you got a pretty wife.

Well mister, all I got is attitude. And I had it all of my life.

Writing this the lyric ‘Pappa go to bed now, it’s getting late. Nothing we can say or do is gonna change anything now’ might be more apt, but as the Boss said. Number Two range was freezing cold, but not so Heytesbury Battle Range, up on top of the Plain where the Army used to let us play on their big boys range now and again if we’d been very good. There were trenches to jump over, electric pop-up targets, and buildings to clear and it was generally all good fun for a growing lad. I met the Special Boat Services guy who invented and luckily for him, patented the SPAS 12, which might have been manufactured by but I can guarantee certainly wasn’t developed by Franchi.

He’d designed this combat 12-bore shotgun to shoot semi-automatically, meaning it would fire every time you pulled the trigger, re-loading itself, and if you pressed a button it worked as a pump-action, I think in case it jammed. It was a long time ago but I think he’d also tried making it fully automatic, so if you pulled the trigger it simply discharged every cartridge in it, but as there were only seven or eight there didn’t seem to be much point, and it was uncontrollable anyway unless you were built like King Kong, or at least like the chunky kinds of guys the SBS hired in those days.

After university I got a job through BUNAC, teaching kids to shoot on a summer camp in Wisconsin, bought a $200 twelve-year-old Chevrolet and a .22 AR7, and had the best summer of my entire life, thanks to a red-haired cheerleader, a lake, free ammunition, my shooting range and Hunter Thompson, who I tracked down to Woody Creek after driving 1,100 miles to get there. The AR7 didn’t last long, not through any fault of the gun, although it did have the fault of shooting high right and didn’t have adjustable sights. About two weeks after I bought it the police showed up at summer camp and told me I wasn’t allowed to have it because I wasn’t a US citizen. Without citizenship I could buy any kind of shotgun if I wanted, or anything that used black powder, maybe a nice .44 of the kind cowboys used to holster, but nothing using a modern smokeless powder cartridge, however tiny compared to a .44. I didn’t make the rules.

They had an odder rule in America anyway. Back in 1934 when Bonnie and Clyde roamed the land the National Firearms Act set a fee of $200 payable to the Bureau of Alcohol. Tobacco and Firearms if you were a citizen and wanted to buy a machine gun. Today that law, and weirdly, that fee, $200, still stands. Even more weird, in 1968 the US Supreme Court decided that that original NFA was unconstitutional. Not because it banned people from having machine guns unless they had a license. Oh dear me, no. If your idea of your inalienable right to the pursuit of happiness happens to include burning through ammunition at 800 rounds per minute then no American court is going to say that maybe that wasn’t quite what the Founding Fathers had in mind. No, ma’am.

The reason the Supreme Court effectively chucked out the 1934 Act was that if you had a machine gun in 1933, then the Act came in the next year and you thought, gosh darn it, I’d better register this shootin’ iron and stay legal, then you’d be incriminating yourself; by applying for the licence for the machine gun you had, you’d be saying in writing that you had a machine-gun, and that’s against the law, bud. Trying to stay legal and register your unregistered gun meant you were saying you possessed an unregistered gun, which you or I might say was, like some other parts of the Constitution, a fact we find to be self-evident. And that fact also violated the individual’s privilege from self-incrimination under the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Get out of that, in the land of the free.

I drove across America un-armed anyway, and nothing ever happened to make that the wrong decision, wherever I went.

And then London, and no decent ranges I could find and arsey London attitudes when I did track them down, and the dismal Stone range, a train ride and a twenty-minute walk away in darkest Kent. I stopped shooting then and didn’t really start again until I took up clay pigeon shooting when I’d moved out to the edge of the M25. All of that pretty much stopped as a regular thing with Dunblane. I didn’t much want to be associated with that, nor the sickening virtue-signaling of the Home Office Minister I wrote to, protesting the confiscation of legal firearms would do nothing whatsoever to stop gun crime. I wish I’d kept the letter he wrote and signed, saying m maybe not really, but the government “had to be seen to” be doing something. Or in code, The Sun won’t stand for it if we aren’t.

For a very long time, I thought that was that. There isn’t any shooting apart from clays and after I lost half a tooth exactly where my cheek met the stock of my rather nice Winchester skeet gun, the prospect of losing more of them somewhat paled. Until about this time last year, when I discovered not only that yes, there actually were still shooting ranges around, but you could join them, go through a monitored probation period, and after that, shoot pretty much any time you chose, at mine anyway. Which even more amazingly, was walking distance from where I live.

I bought myself an air-rifle about ten years ago when thanks to keeping chickens we were plagued with rats. Big rats. They eat chickens if you let them, which I had no intention of doing, and as my very old cat wasn’t stupid enough to take them on alone I had to give him a hand. I thought it was getting a bit too Country Living when I found myself sitting in the sun at six in the morning, wearing only a dressing gown and wellies, cradling a mug of tea and an air rifle, waiting for the rats to come for their breakfast.

Home on the range

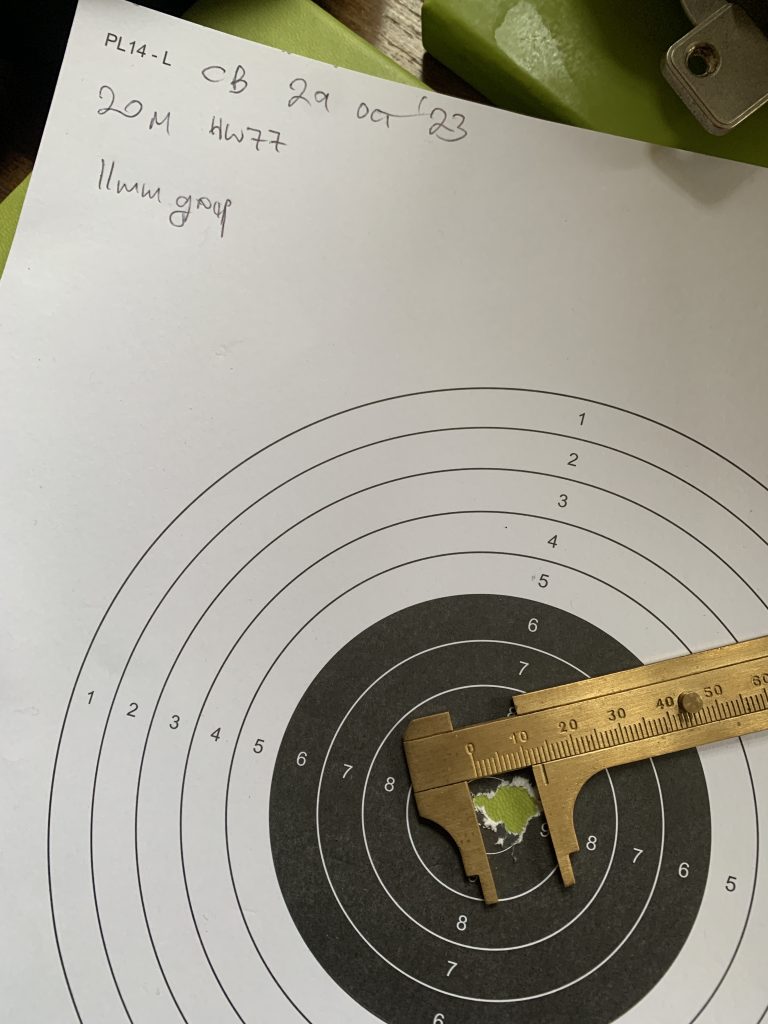

For my birthday last year, I bought myself a better one, a rather beautiful Wierauch 97 with an unbelievable Czechoslovakian telescopic sight that does one thing well: it shoots exactly where you aim it, which if you know anything about shooting at all, you’ll know to be a fairly rare thing. Three weeks ago I managed to do the almost impossible, shooting a possible. In other words, if the bullet did actually cut the line on the target, which it looks as if it did, means 100 out of a possible 100.

My beloved partner likes to shoot some Sundays too and from a standing start, after just a couple of months regularly shoots in the high 90s and about half the time, better than I do. Her challenge is being consistent but then, that’s what shooting is about. Get the group small and in the same place and you can move it onto the bull using the adjustments on the sights; if you don’t shoot consistently then it doesn’t matter what you do, you’ll never get better. It’s about controlling yourself, your breathing, your posture, your relaxation, your mindfulness, I suppose now. All of that. And some of it’s about remembering a summer, with a lake, a shooting range, a flag and a cheerleader called Nancy-Jean.