Once upon a time, in a land long ago, I was at a rodeo.

No, seriously.

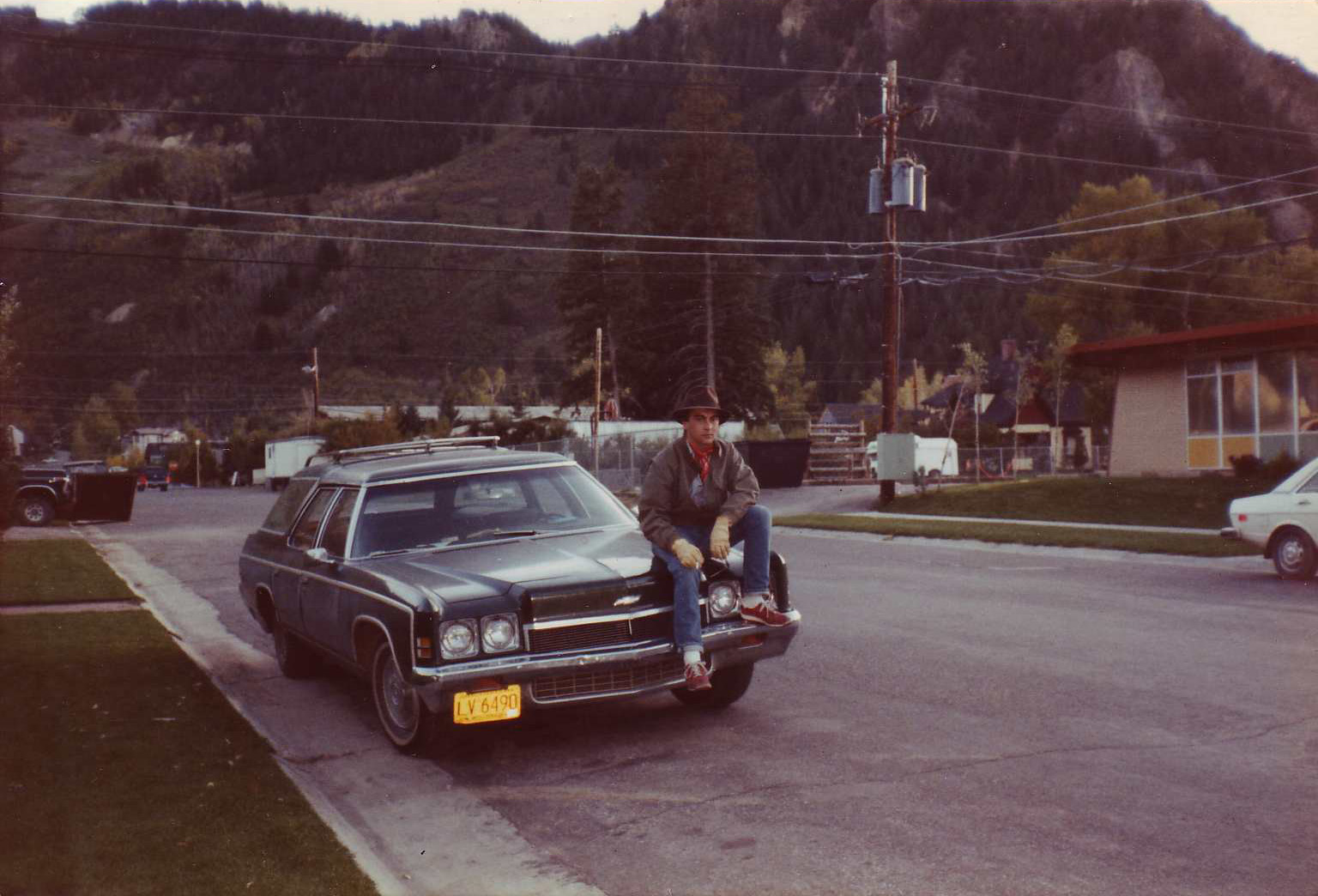

It was in a place called Greencastle, In., and the only way you’ll ever have heard of it is if you work for IBM, know where one of two V1 rockets in the USA are (apart from Werner von Braun’s den, obviously), or you’re an alumni of De Pauw university. Or you know something about Dillinger or the way any old bank robbery in the 1930s got attributed to the famous robbers if the actual robbers didn’t get caught and escaped in a car. Or maybe, like me, you were chasing a red-haired cheerleader called Nancy-Jean and driving a ludicrously big old car that probably extinguished three species on its own.

Anyway, it was a Saturday, Nancy-Jean was out of town, I was staying at her folks’ place in her room with the rainbow painted on the wall (as Werner used to say, ach, it vas all so long

ago…), I’d done a week’s worth of pretending to be in a Springsteen song working in a sawmill the other side of the tracks and apart from golf, which I don’t do because I don’t, there wasn’t a whole lot else to do. As we used to say.

I sat there on the bleachers (oh because that’s what they’re CALLED, ok?) and had myself a darned fine time. The steer wrestling was good. They got a steer and let it loose and anyone who thought they were hard enough grabbed it by the horns and wrestled it to the ground. Then they let it go. They didn’t have a whip or a gun or a stick, just their hands. It looked pretty equal to me.

Look, I know, ok? I’m not like that now. It was the past, it was definitely another country and they did things very differently there. But actually not so much, speaking as someone who had to get a lorry load of bullocks out of a pen and into a truck one dawn at Bridgewater Market. I was fourteen. I learned that bullocks are more scared of you than you are of them but it’s close. That if you twist the ring in their nose they’ll go anywhere you want. And that if you don’t you might end up sneezing your lungs out of your nose after they’ve slammed you into a metal fence and trodden on you.

I still wasn’t gonna go an wrassle a bull and that ain’t no lie.

I just watched and listened. A guy who was about my age now, wearing a cowboy hat, was talking a few feet away. I liked him. He was one of those people who could turn pretty much anything he said into a story and a good-natured one at that.

Even when what he was saying was serious. And sad. He told a woman a few seats away and pretty much anyone else who wanted to hear about his daughter. She’d bought herself one of those fancy Japanese cars, a Honda or a Toyota or something. And in the real world of Indiana back then, you didn’t do that. So he stopped talking to her. It had been months.

He said it was for a reason. Sure, it was a good car. Maybe better than a comparable American car. In fact no, definitely. She was smart. And it was cheaper. But if everybody did that there wouldn’t be no car industry. And that meant Americans, real ones he knew, up in Flint and Gary not even a hundred miles away, wouldn’t have jobs.

I don’t have much sympathy for the people who voted for Trump for a lot of reasons, but this one is up at the front. Actions have consequences. The first time I went to the US all the clothes in shops were from the USA. The second time, 12 years later, I couldn’t find any that were and they were less than half the price. If you buy cheap import stuff I don’t think you have the option of complaining about the lack of jobs at home.

And before anyone writes that off as elitist, that people on low incomes don’t have those choices, they do. They chose to buy a phone made in China and a network data plan instead of a $40 shirt from the USA. But they still need a shirt so they get a $15 one made in Guatamala instead. Funny how that factory closed and there ain’t no jobs here no more. Dang Democrats and their elitist globalisation. Trump all the way.

Tom Petty had to live with some hard promises. Springsteen told us we could count so many foreign ways to the price we paid. And now I’m as old as the guy in the cowboy hat back at the rodeo, I know they were both right. And Trump and his supporters are wrong and always wrong. Because there aren’t easy answers. What you do comes back to you.

Life, as Dr Hook put it, ain’t easy and nothing ain’t free. And cheap stuff isn’t. Sometimes you have to do without the things you want because of what will happen if you get them. Don’t want globalisation? Then don’t buy its products. People like Trump always promise it’s about personal responsibility; Thatcher did it too. But their biggest message was always the opposite: the bad stuff, that’s always someone else’s fault.

I ate a hot dog, watched the men wrassling steers and drove my big old Chevrolet back to Nancy-Jean’s house, up on the hill by the golf course, the good side of the tracks. A week later I drove down to Bloomington to see her, then drove out west on I-70 into my life, leaving her to hers.