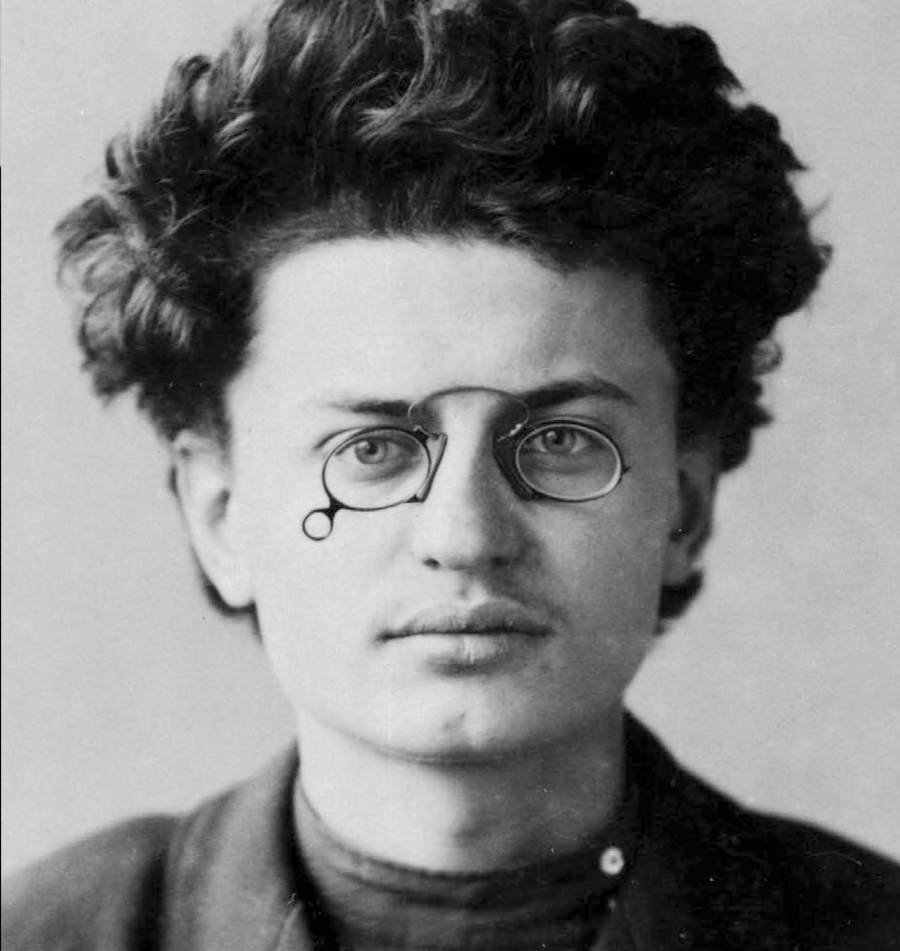

The only thing I learned about Trotsky was a mistake. I hardly learned anything in three years of Sociology at university, other than the fact that you can’t run a car and a Triumph 650 on a student grant and that if you move in with your girlfriend next door to an occasional girlfriend your life will be a lot louder and considerably less fun than the Austin Powers script you had imagined. I don’t know if Trotsky had that kind of stuff to deal with but he had his own problems.

Like living in Mexico. I went there once. The story of that Sunday and the unfortunate misunderstanding in Tijuana is familiar to a select few very close friends and not usually told to people I’ve only just met, in case they wash their hands after shaking mine and their womenfolk’s faces turn to stone as you close for the parting peck on the cheek. More than usual, anyway.

In some ways I wished I’d paid more attention now. After leading a failed struggle (it says in Wikipedia, which has certainly been more useful than nine terms at Bath) the against kindly Uncle Joe Stalin, whose propaganda machine was still creaking on even when I was an undergraduate, Leon Trotsky did some groovy stuff. He got himself deported from the USSR in 1929, for a start. He lead a thing called the Fourth International in Mexico, opposing Stalin and bureaucracy. He thought the Red Army should fight Hitler when Stalin didn’t think anything of the kind and opposed Stalin and Hitler’s Non-Aggression pact, all of which British Soviet fans had airbrushed out of history when I was at school.

Predictably enough, all this didn’t go down too well with Stalin, who ordered Trotsky’s assassination in 1940. With an ice-pick. This was the only bit I knew then. Because it was so ludicrous. I’ve read James Bond. I understand that sometimes when you want to murder someone the ideal tool for the job isn’t available. But I’d have thought that the chances of finding an ice pick in Mexico were fairly slim, especially compared with the rather high chance of someone saying “where on earth are you going with that ice pick, Ramon?”

Last week I talked with someone who’d been shocked about someone else’s behaviour a quarter of a century ago and still regarded the other woman with awe if not admiration. Except I was able to tell her that actually, while all that may have happened it certainly didn’t to that person because I knew for a fact she was in another country at the time. She’d misunderstood something someone had said. A quarter of a century on she still believed it. I was sort of pleased to find it wasn’t just me.