Sorry always seems to be the hardest word.

Yesterday in 1989 I was 32 years younger, but like the man in the song, I can still remember how that music used to make me smile. Usually it was the Fine Young Cannibals, that summer.

But yesterday, November 9th, 1989 what I thought was the biggest, most important thing in my life happened. And Johnny, we’re sorry, because we just wasted it. Because we wanted to.

Quick history lesson for my younger readers. 1945 World War Two ends in Europe, chiefly not actually due to Tom Hanks in any of his incarnations, not Private Ryan nor even the Band of Brothers themselves, but more to do with the unbelievable final advance of the Red Army, which rolled straight through what was left of the Wehrmacht Heer at up to 700 km per day.

All went to plan. The three leaders of the enemies of the Nazis when it suited them, Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill agreed at Yalta in February 1945 that the USSR got to decide what happened in Eastern Europe. As the Red Army occupied most of Eastern Europe at the time that made sense, even if people like Isiah Berlin (who I always confuse with Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil, which never, ever helps) thought determinism and historical inevitablity – the idea that things are the way they are because of the things that made them the way they are – was implausible.

Isiah Berlin. How many army divisions has he?

Whether or not Stalin actually said that about the Pope doesn’t matter; in 1945 Stalin had plenty of army divisions, outnumbering the German army four to one. One of the first things they did after killing lots of Germans was to split Germany in half, followed by occupying Poland, just in case it was used as a corridor to attack the USSR. If you see something with Made In West Germany stamped on it you know it was made before 1989. All the countries around the USSR had to be friendly to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics according to the USSR, and if they weren’t then the Red Army would show them how to be. As it did in Hungary in 1956.

By 1961 it had became obvious to the that people in an East Berlin de facto controlled by the USSR didn’t like living there so much as they thought they’d like to live somewhere a bit further West, which wasn’t. Three and a half million East Germans, one in five of the population voted, peaceably, with their feet and left.

A river runs through Berlin, the Spree, but that wasn’t enough to stop the exodus. The German Democratic Government built a concrete wall, with armed guards and searchlights and a strip of sand raked so that footprints would be obvious and just to make it clear they weren’t playing, outside Berlin anti-personnel mines were dug into the sand. What Churchill had described as an iron curtain was made of concrete. it split Berlin in half but more than that, it split Germany in half. More than that, it split Europe in half. Over a thousand people were killed getting out.

Kennedy came to Berlin and made a speech about freedom, holding the Wall as its antithesis, only slightly marred by the fact that as a non-German speaker, and someone who clearly didn’t know as much about the country as he wanted to be seen to identify with, he didn’t know that “Ich bin ein Berliner” actually meant “I am a coarse-cut pork sausage.”

“Every stone bears witness to the moral bankruptcy of the society it encloses”

Although I hated to agree with Margaret Thatcher who said that about the Wall, I had to acknowledge she was fairly well-qualified to speak about moral bankruptcy. What happened next came out of the blue, at least to me, and to someone I used to know who was there. She was working for the BBC and on the spot, unlike the BBC man with the microphone, who did the broadcast but couldn’t see what was happening. She told him, from on the spot, what was. He told the world, on air. He got famous for the broadcast. She didn’t. But what was happening was even more unbelievable.

People started tearing the wall down. The East German guards shot dead the first person to go near the Wall in 1961. In 1989, for the first time in nearly 30 years, they didn’t shoot at all.

Here in East Anglia three hundred years ago Mathew Hopkins decided he had the ability to find witches, and that he was better at it than almost anybody else except John Stearne. Between them they had hundreds of people, mostly women, tortured and after confessing to hanging-out with the Devil, killed. One story goes that at the end of this nonsense, with people writing to Hopkins much in the same way as they later did with Jimmy Saville to fix it, one vicar who found himself accused of witchcraft and told to present himself to trial simply refused to go. He waited for the watch or the pre-Elvis Costello version of the New Model Army or anyone else to come and arrest him and take him for trial and utterly predictable verdict and death.

But nothing happened.

Nobody came, as soon as one person had stood up and said no, this is nonsense, I’m not doing this any more. The fall of the Wall reminded me of that.

The Peace Dividend

You don’t hear about that now. Because we wasted it. Media used to talk piously about all the money we could save now we didn’t have an enemy and didn’t have to have James Bond and Dr Strangelove and B52s tooled-up with nuclear bombs in flight on constant airborne watch, with their pilots wearing one eye patch so when they were blinded by the brightness greater than a thousand suns they still had one eye left to blow-up the rest of the world and all the rest of it. All that was going to stop. We’d suddenly said this is nonsense. We’re not doing this anymore.

By 1992 the US Air Force had mostly left Suffolk, where they’d been on watch since 1943. But the rest of it we rubbished. We just stopped talking about nuclear bombs. They’re still there. James Bond died in his latest movie, just three decades after the Wall came down. As for military spending, since 2001 we’ve spent far more on armies than we spent from 1945 to 2001, invading countries on made-up pretexts and losing to a bunch of extremely militant hippies in beards and sandals with a few rifles. All that kit, all that money and all those lives spent so that we could continue to have an enemy. After all, where would we be without someone else to blame?

Nobody knows the trouble you feel

Nobody cares, the feeling is real

Johnny, we’re sorry, won’t you come on home?

We worry, won’t you come on?

What is wrong in my life

That I must get drunk every night?

Johnny, we’re sorry.

Roland Gift/David Steele: Universal Music 1989

Postscript

A German woman born in 1976 got in the car with her mother when the wall came down. She’d been told about the pretty town her mother came from, before the war. They hadn’t ever been able to go there, because it was in the other half of Germany, the Eastern half. With the Wall down and the USSR collapsing they drove East into a different world.

They forgot that the past is a different country. They do things differently there. They found the place with the same name, but they never found the town. First the Red Army had flattened it. Then the Wehrmacht had counter-attacked. Then the Red Army rolled through once and for over thirty years, all. There wasn’t much left of the town by then. What there was fell to bulldozers and got buried under 1950s concrete tower apartment blocks.

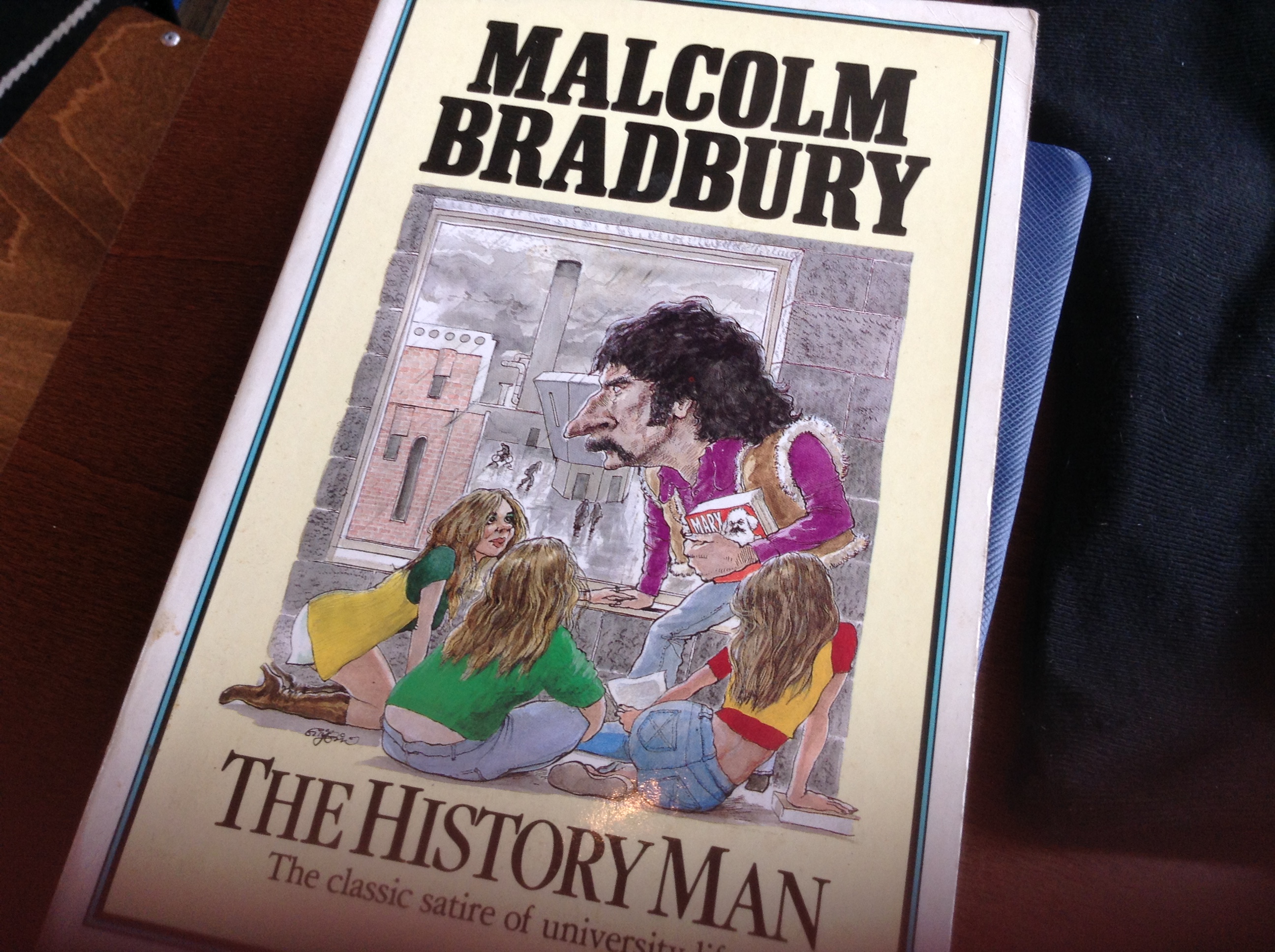

I think of the blond teenage girl in the 1990s car, her mother next to her at the wheel, parked up and tired, all their landmarks gone, looking at stark concrete buildings as the dream of little wooden-framed buildings vanished through the windscreen. And it feels to me the same as the feeling about the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain falling apart. Hardly anyone can even remember it now and like Mathew Hopkins, the Knights Templar, Smiley’s People, the Spy Who Came In From The Cold, Rutger Hauer’s Tears In Rain speech in the original Bladerunner film – that was then. It all changed. Maybe there isn’t any historical inevitability and it just doesn’t matter anyway. Or maybe, just like being accused of consorting with the Devil by Mathew Hopkins, Isiah Berlin and Howard Kirk got it wrong; in fact there was only ever going to be a single, utterly predictable outcome.

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties.

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties.