I went to see Dunkirk last night. Not, as Daphne Du Maurier would have it, again, because I’ve never been there. Dieppe, definitely. Boulogne, bien sur. Calais, ‘course. But not Dunkirk.

I went to see Dunkirk last night. Not, as Daphne Du Maurier would have it, again, because I’ve never been there. Dieppe, definitely. Boulogne, bien sur. Calais, ‘course. But not Dunkirk.

A friend’s father did in 1940. He had a great day or two smashing-up lorries. British army lorries. To stop the Wermacht Heer getting hold of them. He drove them off a cliff, jumping out at the last minute, him and a mate, like James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause. And before anyone tells you ‘they did though, they had a true and noble cause,’ I’m pretty certain, not having a Ouija Board, that he’d be the first person to say bollocks to that. He was 20, he’d joined because he could see there was going to be a war and he needed the money. There was a Depression. He’d had to get down from Newcastle to London before that. His brother was a Jarrow Marcher.

And then the fun stopped. He was on the beach for a week. He was in the water, at the end of a human pier, for a lot of that time. He gave up his place on a little ship that came in to put someone else in the boat and off the beach and away safe to Blighty giving up his place in the queue. The little ship was bombed. Everyone who he’d saved was killed.

I don’t know what he’d have made of the film. It wasn’t entirely what I was afraid it would turn out to be, a moronic Good vs Bad Brexit hymn. The film showed most of what it was, an almighty balls-up, a catastrophic defeat from which ordinary people doing extraordinary things selflessly managed to salvage something of the core of a force to fight another day.

Something of. After Dunkirk generals were sacked, troops were throwing their rifles out of train windows as they steamed away from Dover station, whole regiments were amalgamated and re-formed, not just for administration but because a feeling existed that a lot of the retreat had come about because of the way things had been run.

But it’s a film, innit? It’s not supposed to be a documentary. The pace was relentless. Both of us came out of the cinema tense and with aching backs from the noise and the stress. We doubted it was maybe precisely the same amount of stress as actually being at Dunkirk, but we thought that frankly, for an evening out we’d pretty much gone through the mill. Especially in Dorchester.

We’d had a decent Thai meal, an achievement in itself. We’d managed to mute the assorted ‘fucks’ and ‘shits’ that spray the speech of people d’une age certain, more especially the women after, as Howard Kirk would put it, we re-colonised the language in actualising ourselves. She did mostly, anyway. I think the next table caught some. We’d had the sense to book the tickets in advance and also to wear hats as it was bucketing. And it was mostly a decent film.

Except for the end. I mean, s**t. F***ing Elgar FFS? Seriously? F***ing absolutely seriously? And not just any old Elgar but yer actual pean to Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, in case you’d somehow missed the point. (And obviously, no irony whatsoever in the most English of composers writing music as a tribute to a German, being used to celebrate an imaginary triumph over German forces. None).

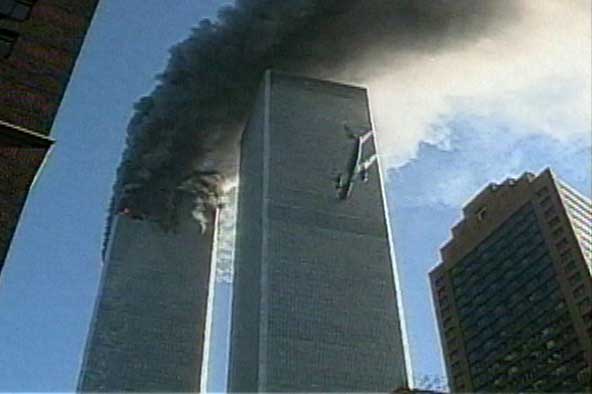

And no, as in heroic. It doesn’t have a T in it. The hero, in his RAF Spitfire ( the film was very insistent on it being a Spitfire, made of metal, not a Hurricane, made mostly of fabric. This will matter. Test later), out of fuel, benefits from a bit of actually very good acting by the rescue boat skipper who dupes Johnny Boche into flying straight across the hero’s dead-engine flight path.

Rat-tat-tat-tat!! Ach Himmel!! ARGHH!!!

And so on as Commando magazine taught us all.

His prop spinning uselessly, our hero has to land on the beach at Dunkirk. But wait! His wheels won’t go down!!! Must have picked up a packet of flak in that last scrape! Better pump the wheels down by hand before the kite prangs.

And this, for me, is where it got silly. I’ve known people who have terminally messed-up fighter plane landings. One thing that any horse rider or even walker knows though, without being a pilot, is that on a beach, some sand is hard and other sand is soft. And you can’t always tell by looking at it. So if you’re sitting on a couple of tons of scrap metal doing about 100mph, personally I think the last thing I’d do would be to put wheels down which if the ground was soft as well it might be would be pretty much guaranteed to set the remains of the airplane cartwheeling across the landscape. With me still in it.

But the wheels got down, Elgar struck up, just a hint at first, then when the composer thought ‘got away with it’ a proper bit of Nimrod. You know the one.

Dah-da-daaaaah daaa. Dah da daaaaah daaaa……. Think any Royal nonsense at Westminster Abbey and you’re pretty much there. But sillier was to come.

Desperate not to let Jerry get hold of an intact Spit, our hero whips out his flare gun, fires it into the cockpit and stands back to watch the crate go up in smoke, which it obligingly does. Except it’s supposed to be out of fuel, so quite what it is that’s burning isn’t at all clear. Even the wings are burning, which for metal wings is a pretty good trick.

The engine wasn’t burning though, mostly because in the last flame-filled shots, there wasn’t one, just what looked like a broom handle holding the propeller onto the flaming remains of the fuel-less metal-that-burns airplane. Cue credits. And a ha’p’orth of tar. But according to my passenger on the midnight drive home, past the ghosts of Romans and our teens, I was just talking bollocks caviling at that.

Still, for a big budget film at least the Americans didn’t come and win it for us.

Once upon a time something happened here. The army threw everyone out. On VE Day the army blew up the derelict pub. They wanted, to build a celebration bonfire. The pub wasn’t supposed to be derelict; someone took a few potshots at it, some time during the war.

Once upon a time something happened here. The army threw everyone out. On VE Day the army blew up the derelict pub. They wanted, to build a celebration bonfire. The pub wasn’t supposed to be derelict; someone took a few potshots at it, some time during the war.

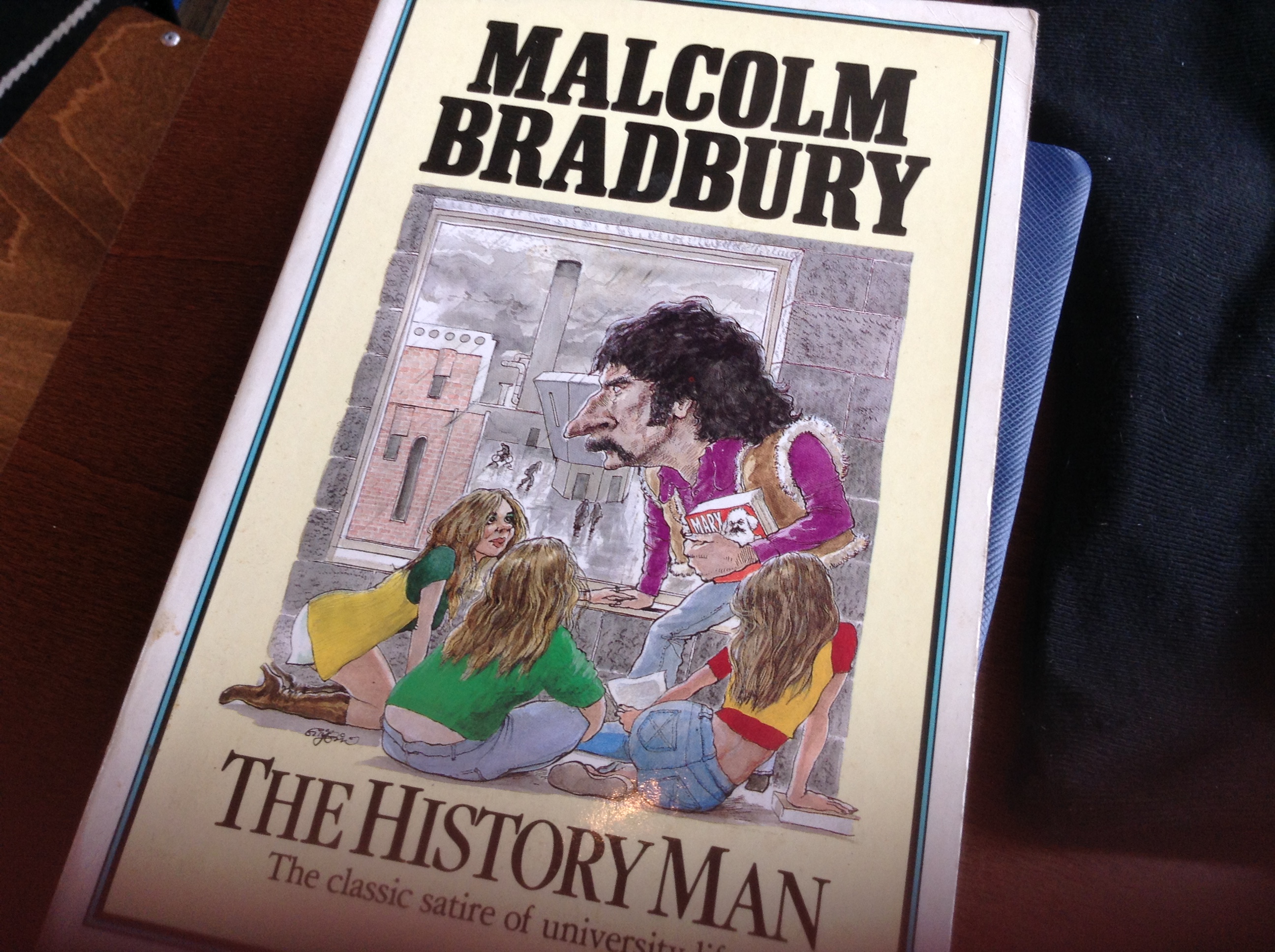

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties.

Howard Kirk was a Sociology lecturer who believed that conflict was always good. That right would triumph. That right was historic inevitability and Right was wrong. I didn’t share that view then, but I was young and fairly stupid. As a friend told me the other night, I was far too self-absorbed in my twenties. I went to see Dunkirk last night. Not, as Daphne Du Maurier would have it, again, because I’ve never been there. Dieppe, definitely. Boulogne, bien sur. Calais, ‘course. But not Dunkirk.

I went to see Dunkirk last night. Not, as Daphne Du Maurier would have it, again, because I’ve never been there. Dieppe, definitely. Boulogne, bien sur. Calais, ‘course. But not Dunkirk.